Top 100 Albums by Black Artists

This may be extremely difficult for Jann Wenner and other faux elitist music journalists to believe, but there are at least 100 albums by Black artists worth listening to. And Bob Dylan had not a damn thing to do with any of them.

There are a few rules that I kept in mind when compiling this list.

1

Contains albums in the realm of R&B and Soul, as I define the genres. There might be lists of other genres like reggae and disco forthcoming, so the albums I like by artists from those genres will be logged over there.

2

No straight up compilations or unofficial mixtapes included here. Greatest hits collections will be listed elsewhere.

3

Artists must be predominantly Black and/or the focal point of the group is Black, like Sly and the Family Stone or Sade. I list my favorite white albums in a different section of this site.

79

Bell Biv Devoe

"Poison"

1990

“Ain’t nothin’ but a thang that we gonna do / Everybody’s always talkin’ ’bout the N.E. crew.”

That “everybody’s always talkin’ ’bout” line was true—for about a good 14 minutes. But what a moment it was. During that brief, glorious window when every member of New Edition dropped solo projects away from the mothership (Ralph Tresvant and Bell Biv DeVoe’s debut albums, Bobby Brown’s "Don’t Be Cruel", and Johnny Gill’s "Johnny Gill"), the N.E. crew became a full-blown juggernaut of high-quality Black pop. From the late ’80s into the early ’90s, they dominated the charts with jams you could dance and mek luv to with equal intensity.

Let’s be honest, though: when the second-tier members of New Edition announced they were doing an album together, expectations weren’t exactly sky-high. We knew Ricky Bell could sing. We knew Michael Bivins… well, couldn’t. And we weren’t even sure what Ronnie DeVoe brought to the table. But none of that mattered once The Bomb Squad got involved. With the same sonic sledgehammer they used to build some of the most iconic rap albums of all time, they helped ensure any talent potholes were paved over with bombastic, high-octane funk.

If you swap out the original version of the album opener “Dope!” for the vastly superior “She’s Dope! (EPOD Mix)” and skip the unnecessary extended remix of “Poison” tacked on at the end, what you’re left with is a tight, nine-track, no-skips-needed record that can hold its own against nearly anything released in 1990. And that was a competitive year—massive sellers like "Please Hammer Don’t Hurt ’Em", "The Immaculate Collection", and Mariah Carey’s debut were all out at the same time. Poison still managed to be one of the year’s top sellers, ending up at #24 on the year-end chart.

I’m a sucker for music that’s fun just for fun’s sake, and Poison delivers in spades. I never take the album’s sometimes misogynistic lyrics too seriously—especially since, once that CD goes on, the one shaking “a big butt and a smile" is me. The album is seven straight bangers deep before it cools down into two perfectly solid ballads. Highlights include the irrepressible “Poison,” the freaky-funky “Do Me!”, the swaggering “Let Me Know Something?!”, and the high school punctuation-flex anthem “B.B.D. (I Thought It Was Me?)”.

Speaking of punctuation, I’m sure B.B.D.’s old English teacher was tickled pink by her alumni’s dedication to question marks, though I have to point out that some of those sentences aren’t actually questions. But errant punctuation aside, "Poison" was a shockingly strong, relentlessly entertaining party record.

We can’t say the same, of course, for B.B.D.’s crummy follow-up. In the words of the trio themselves: “Wrong move, you’re dead!?” (Pun-ctuation intended.)

78

Vesta

"4 U"

1986

Remember how cute and innocent Janet Jackson looked as Penny Woods on "Good Times" in the late 1970s? She seemed like she couldn’t hurt a fly if she tried. Even on "Diff’rent Strokes" and "Fame", Janet was cute as a button—doe eyes, pinchable cheeks full o’ nuts. But apparently, all those hot iron moments she suffered on "Good Times" turned little Penny into a ruthless, heartless capitalist who would crush anyone standing in the way of her rise to superstardom.

Unfortunately, Vesta’s car stalled on Janet’s Parkway to Pop Stardom, and it got towed away and demolished before she had the resources to move it somewhere safe. Because "4 U" had the misfortune of competing with the juggernaut that was "Control"—on the very same label, no less—it was pretty much doomed from the start.

Yes, I blame Penny for this.

The cold truth is that "4 U" was a well-crafted, superbly produced, and masterfully sung album that never had a chance. It didn’t even crack the Top 20 on the R&B album charts—not because of the music, but because Vesta was on A&M Records, and A&M Records was too busy funneling every penny (pun intended) into Janet’s marketing machine. Vesta never got the budget, the push, or the support she deserved.

"4 U" is remembered mostly for the passable torch song “Congratulations,” but that’s just one piece of a much larger, richer puzzle. The album is packed with high-quality dance tracks (“All On You,” “4 U”), silky mid-tempos (“Hunger”), and some truly stunning ballads—sung with a panache and vocal power that set Vesta apart from nearly every other female singer of the time. For me, “Running Into Memories” and “Sweet Sweet Love” are the standouts here and remain two of the best songs in Vesta’s entire discography. (How a song as perfect as “Sweet Sweet Love” isn’t placed on the same soul pedestal as “Here and Now” or “Sweet Love” is truly beyond me.) But most folks never got the chance to enjoy this album, because it was buried near the bottom of A&M Records’ priority list. A shame. A low-down, dirty shame.

I guess when Janet said she was in control, we didn’t realize she also meant the record company.

77

The Emotions

"Flowers"

1976

When The Emotions signed with Stax Records, they didn’t exactly set the world on fire. They had a few decent hits, but getting the attention they deserved was nearly impossible while competing with the likes of Sam & Dave, soul titan Otis Redding, and Isaac Hayes, who was quickly becoming the genre’s biggest star. By the mid-seventies, Stax was bankrupt—and so, seemingly, was The Emotions’ career.

That changed when their new label, Columbia, paired the Hutchinson sisters with Earth, Wind & Fire’s Maurice White and his brilliant songwriting and production partner, Charles Stepney. Stepney, a respected musician, arranger, and member of psychedelic soul outfit Rotary Connection, helped reinvent their sound. Together, he and White swept aside the saccharine stylings of 60s girl groups and handed The Emotions rich, layered, meaty soul to sink their heavenly harmonies into. And the results were stunning.

From the funky brilliance of “I Don’t Want to Lose Your Love” to the breezy “No Plans for Tomorrow” to the title track “Flowers,” the album doesn’t miss a beat. The production is immaculate, fusing jazz, African rhythms, and R&B—a true testament to Stepney’s attention to detail. And the Emotions are in peak form throughout, their voices both confident and celestial. When it comes to song quality, this album is pure Sam Goody.

My only qualm? The album’s stingy runtime—just seven full songs, none over 4 minutes and 30 seconds. Why so short? Instead of those two inspirational interludes, how about one more whole 'nother track? Still, "Flowers" is a gorgeous musical statement. Though Charles Stepney passed before he could witness the album’s success, his influence is all over it. And while The Emotions would go on to even bigger hits with Maurice White at the helm, everything truly blossomed here—with "Flowers".

76

Rick James

"Throwin' Down"

1982

I had to pull out a calculator just to confirm that 1982 (the year "Throwin’ Down" was released) minus 1978 (the year Rick James’ debut "Come Get It!" dropped) equals four.

FOUR.

So how the hell was "Throwin’ Down" already Rick’s sixth album?

One reason, I think, is that while Rick James was a veritable giant of R&B and funk—with a trainload of classics—his albums weren’t exactly intricate concept pieces. Many of the sounds from one track bled right into the next. Sometimes whole arrangements felt like reworked versions of ideas he’d already laid down on earlier records. But that didn’t matter. The music slapped. It served as the background to our early-’80s lives.

To us, Rick James was so much more than “Super Freak,” just like I imagine Neil Diamond means more to white folks than “Sweet Caroline.” (I have no way to verify that, though.)

"Throwin’ Down" follows in the footsteps of "Street Songs", Rick’s biggest record, which had hit just one year prior. The formula is mostly the same: funky grooves with a side of social commentary, a couple of slow jams, and one jazzy outro that sounds like a demo someone forgot to finish. There’s even Teena Marie wailing in the background on “Happy,” much like she did on "Street Songs’" banger “Fire and Desire.” But if I’m being honest, "Throwin’ Down" as a whole feels more solid to me that its predecessor.

A big reason is “Standing on the Top”—Rick’s collaboration with the Temptations. Let’s be real: it’s a Temptations record featuring Rick James. And it’s glorious. My only gripe is that Motown only included the single version here—it barely clocks in at four minutes. I needed the full 10-minute version, the one the Temps put on their "Reunion" album. (Back in the day, I had to go buy that whole album just to get the extended cut, only to discover that “Standing on the Top” was the only Rick James production on there. I should’ve sued Motown for emotional distress.)

Despite its quality, "Throwin’ Down" didn’t get the push it deserved. The album wasn’t promoted properly, largely because Rick—at the height of his drug-fueled volatility—was making it nearly impossible for the label to do business with him.

There’s a now-legendary story that Rick, furious about the album’s poor performance, stormed into a Motown exec’s office, did some lines of coke right there on the desk, pulled out his dick, slapped the exec in the face with it, and calmly walked out. The stunned exec turned to an assistant and said just two words:

“Lionel Richie.”

Motown instantly redirected their promo dollars toward Richie’s "Can’t Slow Down", which went on to become the second-biggest album of 1984 and won Album of the Year at the Grammys. Meanwhile, Rick’s career began its steep descent.

1983’s "Cold Blooded" was decent, but the damage was done. His musical output never fully recovered—at least not until Dave Chappelle and Charlie Murphy resurrected his legacy with one phrase:

“I’m Rick James, bitch!”

But long before the punchlines and memes, there was "Throwin’ Down"—a record that still holds up as a crucial part of Rick’s legacy. The funk was thick, the vibe was raw, and for us little Black kids growing up in his shadow, Rick James was it and we love him for moving our feet and spicing up our lives.

Yes, cocaine is a helluva drug.

But Rick James’ music? That was one helluva good trip.

75

Alexander O'Neal

"Hearsay"

1987

Christmas can be a tricky time for kids—especially for those of us who grew up during the topsy-turvy Reagan years, when Trickle-Down Economics never quite trickled far from the top. Though I came from a military family, both my parents often worked two jobs to keep up with the suburban dream—one that many Black middle-class families had somehow tricked ourselves into believing was ours outright.

Some years, the living room overflowed with so many presents they couldn’t all fit under the tree. And then there were the leaner Christmases—like the one where I got two pairs of pants, some shirts, a few pairs of tube socks, and some candy. As I got older, the holiday naturally became a little less magical for all involved. So in 1987, when I saw just one big box and one small one under the synthetic tree with my name on them, I braced for another “Lollipop Christmas.” I had no idea it would end up being the most memorable—and life-altering—Christmas of them all.

Inside the big box: an early-model CD player. In the smaller, slender package: my very first CD—"Hearsay" by Alexander O’Neal. Black Kris Kringle (aka my dad) had really made a list and checked it twice because there was nothing in the world I wanted more than this new music box that all the kids were talking about but none of them had. None except me.

When it comes to full-length albums produced by Jam & Lewis, "Hearsay" easily ranks in the Top 5. It fires on all cylinders—immaculate songwriting, pristine production, melodic richness, and just the right touch of funk. Alexander O’Neal delivers with power, finesse, and clarity, matching the duo’s intricate arrangements beat for beat. There isn’t a weak cut on the album, and it’s one of the rare records where the interludes aren’t just filler—they matter. They tie the project together and actually enhance the overall listening experience. In fact, the album feels incomplete without them. Standout tracks like “(What Can I Say) To Make You Love Me,” “The Lovers,” “Criticize,” and “Sunshine” are top-tier jams, elevated even further by the angelic background vocals of Lisa Keith.

"Hearsay" built on the promise of Alexander’s self-titled debut and didn’t just meet expectations—it surpassed them. It delivered his sole #1 hit with the funky-monkey jam “Fake,” and gave us arguably his best ballad in “Crying Overtime.” Artistically, I’d go as far as to say "Hearsay" stands just a half-notch below "Control" as the most effective and enjoyable concept album to hit the R&B charts in the ’80s.

Soooo blessed that my dad and Alexander O'Neal teamed up in 1987 to give me the most holly jolly Christmas a boy could ever dream of!

74

Erykah Badu

"Worldwide Underground"

2003

Do people still like legendary Funny Black Erykah Badu? Last I heard, the BeyHive left her smarting from tens of thousands of digital stings for daring to say something slick about BeeYawnSay. Things got so bad that she had to call for backup: “To Jay Z. Say somethin Jay. You gon’ let this woman and these bees do this to me??” Mayday! Badu definitely got the wrong-ass Bee stuck in her bonnet that day.

Back in the ’90s and 2000s, Black queens loved them some Erykah. "Baduizm" was a mainstay at every bougie Black cocktail party Harlem could hold, and Black Marys collectively lost their minds when “Tyrone” hit the radio. "Mama’s Gun" earned well-deserved acclaim for its artistic growth. But for me, "Baduizm" was just aiight—too monochromatic and even-keeled for my taste. And "Mama’s Gun"? That’s an Airplane Album: you gotta fly far away from it for a few years, then circle back to truly appreciate its expansiveness. In all, I was never bowled over by Badu or her brand of Bohemian abstruseness, so I quietly tuned her out.

By 2003, I’d moved out of the country, so there was no need to keep pretending I was into her—like I did at those Brooklyn house parties where you were obligated to bob your head to her songs or risk being asked to leave. I had long stopped following Badu’s movements, so I’m not even sure how or when I stumbled across "Worldwide Underground" here in Colombia. All I know is that I downloaded it and was pleasantly surprised. Sometimes, I don’t want my music obligating me to grab a pencil and decode anagrams. Sometimes I just want to be entertained—and that’s what "Worldwide Underground" did. For the first time, Erykah felt like a real person from this planet and not some underworld creature that emerged from a manhole on Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard.

Her signature quirkiness was still on dazzling display on “Bump It,” “Back in the Day” (featuring Lenny Kravitz—though I don’t hear him singing anywhere), and “I Want You,” but gone were the kooky cryptograms and bewildering lyricism that wasn’t nobody tryna understand. I’d almost categorize this album as—dare I say it—party music. Yes, some of the themes were still serious, like on “The Grind” and the album’s banger “Danger,” but the overall vibe was: light up the love flower and bob your head. (If Badu had released this while I still lived in Brooklyn, I could’ve stopped faking smiles and doing that tired shoulder-shrug dance just to stay invited.). The album ends with a revamped version of “Love of My Life Worldwide,” featuring solid contributions from Bahamadia, the late Angie Stone, and King, er, Queen Latifah. This is one of my favorite jams on the set.

I get how critics may have seen this EP as a detour from the dense, layered, important music of her earlier albums—but for once, I was happy to see Badu lighten up and set aside the mystical mumbo jumbo that sometimes flirted with straight-up pretension. Of course, in 2008, she gave me and my simple tastes the middle finger with "New Amerykah Part One (4th World War)"—a bold, ambitious, and borderline unintelligible record. The Chi-Raq of her discography. She returned to more accessible territory with "New Amerykah Part Two (Return of the Ankh)" and got her fun on once again with the enjoyable 2015 mixtape "But You Caint Use My Phone". But for my money, "Worldwide Underground"—perhaps not her deepest statement—is her most satisfying one.

73

Tony! Toni! Toné!

"House of Music"

1996

If you want to get me hot under the collar, just say something shady about Raphael Saadiq. I swear, there is no one more peace-loving than me on God’s green earth—but one of the few things that will get me to square up and box a nigga is hearing him badmouth Mr. Saadiq. I’m not proud of it, but I will go to jail behind that man. And here’s the irony: I’m not even a diehard fan of Tony! Toni! Toné! or his solo work or Lucy Pearl. Crazy, right?

At times, 3T's music felt a little too tribute-heavy for me. “Thinking About You” was too Al Green. “If I Had No Loot” leaned too much into Prince. “Let’s Get Down” had a little too much "Smells Like Teen Spirit" bleeding through it. But even when the influence was heavy, it was still enjoyable—and more than that, I could always feel the deep reverence for musicianship in everything Saadiq touched. He never just made music—he crafted it.

That reverence is especially evident in his production for other artists. And when it comes to 3T, they’re one of the rare groups who pulled off the near-impossible:

1. Their music got better with each release.

2. They quit while they were ahead.

Only The Police can make a similar claim.

Their final studio album, "House of Music", is the pinnacle of their sound—more mature, more cohesive, and more consistent than anything they’d done before. Standout tracks like “Loving You,” “Still a Man,” “Don’t Fall in Love,” and “Party Don’t Cry” shine bright, but honestly, the whole album deserves a no-skips treatment. While most male R&B artists at the time were chasing the boot-knocking trend, 3T stayed grounded. They made music as a band—a cohesive ensemble—rather than just a few dudes crooning over producer-built tracks.

Yes, Raphael was the creative nucleus, but don’t overlook the contributions of the late D’Wayne Wiggins. His presence on "House of Music" adds depth and balance, making this album a true group effort and not just a Saadiq showcase.

"House of Music" stands at a crucial crossroads—the final breath of classic soul before the full emergence of neo-soul. It bridges the two with elegance and authenticity. And alongside Mint Condition, Tony! Toni! Toné! represents the undeniable end of the Black R&B band era. Their fingerprints are all over what came after: Musiq Soulchild, John Legend, Alicia Keys and many others owe a debt of gratitude to 3T. They may have put the instruments down, but their legacy still rings out.

72

Meshell Ndegeocello

"Peace Beyond Passion"

1996

Madonna took a chance on Meshell Ndegeocello when she signed her to her fledgling Maverick Records vanity label back in the early ’90s. Ndegeocello’s debut album, "Plantation Lullabies", received heavy critical acclaim but almost no airplay—mainly because radio programmers had no idea what to do with her. Was she R&B? Jazz? Alternative? Dance? Adult Contemporary? None of the above? Her lyrics were often too confrontational for Iowa soccer moms, and her look was far too butch for an industry obsessed with convention. So America, predictably, took a pass.

An attempt was made to commercialize her when she was paired with John Mellencamp on his #3 pop hit “Wild Night.” But that success didn’t deter Ndegeocello from doubling down on her fearlessness. On her 1996 sophomore album, "Peace Beyond Passion", she launched a direct and blistering critique of America’s moral hypocrisy—particularly its religious puritanism. With songs that explored homosexuality, racism, and abuse, Ndegeocello wasn’t just courting controversy—she was stoking it. Let’s be real: she practically dared the industry to blacklist her. I mean, good luck getting an invitation to The Arsenio Hall Show with songs titled “Deuteronomy: Niggerman” and “Leviticus: Faggot.”

But what Meshell bought with this album was her freedom. She became a critics’ darling, producing not only searing indictments but also soul-stirring artistry. Tracks like “Ecclesiastes: Free My Heart” and her gender-intact cover of Bill Withers’ “Who Is He and What Is He to You?” showcase her interpretive depth. (Unlike Gladys Knight & the Pips—whose fiery interpretation is the definitive version of this song—Meshell didn’t bother to switch the gender.)

The album closes with the gut-wrenching spoken-word piece “Make Me Wanna Holler,” a nine-minute chronicle of her parents’ tragic relationship. It’s not just personal—it’s brave. And of all the records on this list, "Peace Beyond Passion" may be the most uncompromisingly authentic. Grammy-nominated and deserving of a much larger audience, it’s a masterclass in how to sacrifice mainstream appeal for enduring truth.

(For the record, Meshell’s since won three Grammys—including two in a category I didn’t even know existed: Best Alternative Jazz Album.)

71

Johnny Gill

"Johnny Gill"

1990

I remember the very moment I decided to buy Johnny Gill’s debut CD. My mother and I were in Tower Records, and through the speakers came the chorus of a smooth ballad that made me wanna shoop right there in Fiesta Mall. When the verse kicked in, I instantly recognized that unmistakable baritone—it was Johnny Gill.

Now, I had been thoroughly underwhelmed by “Rub You the Right Way” and had no intention of spending money on the album housing that song. But hearing the deep cut “Giving My All to You” that afternoon changed everything. I was sold. And I was right to be.

In the battle of producers that took place on "Don’t Be Cruel"—L.A. & Babyface vs. Teddy Riley—the former emerged as the clear winners, despite “My Prerogative” being a certified career single. But on "Johnny Gill", a new match is underway: L.A. & Babyface in one corner, and a razor-sharp Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis in the other. And this time, the fight’s too close to call.

From the red corner, Babyface comes out swinging with the excellent “Fairweather Friend,” while “Never Know Love” offers more of the same—solid, but not a revelation. “My, My, My,” Gill’s signature ballad, is smooth and well-crafted, though it’s admittedly lost some of its shine over the years.

From the blue corner, Jam & Lewis deliver “Rub You the Right Way,” which I’ve only recently come to appreciate. It’s fine. But then they throw two weak jabs with “Lady Dujour” and “Let’s Spend the Night”—surprisingly limp compositions for a team of their pedigree at the peak of their powers.

But then—redemption. The one-two punch of “Wrap My Body Tight” and “Giving My All to You” knocks the wind out of you. These are the album’s true high points. Add to that Nat Adderley Jr.’s sleeper gem “Just Another Lonely Night,” and the deep cuts start to overshadow the singles.

It’s clear neither production camp handed over their best work—Jam & Lewis were saving their fire for Janet, while Babyface’s most inspired writing was reserved for chicks like Toni Braxton and Tevin Campbell. But even their second-tier material was still operating at a level far above most of their peers.

"Johnny Gill" is ultimately a mishmash of mostly good songs, strung together by the one thing that keeps the whole project from unraveling: Gill’s inspired (if sometimes overwrought) vocals. His voice doesn’t just sing the songs—it glues them together.

So who wins the Producers Showdown? Due mostly to the strength of “Wrap” and “Giving,” I’m giving this one to Jam & Lewis. But the true champion here is Johnny Gill himself—who had the good fortune to be the baloney in a hot-producers-of-the-moment sandwich.

70

Marvin Gaye

"Midnight Love"

1982

Tragedy seemed to follow Marvin Gaye at every turn—from the onstage collapse and eventual death of his singing partner Tammi Terrell, to his bitter and very public divorce from Berry Gordy’s daughter, to his spiraling drug addiction and eventual murder at the hands of his own father. And yet, despite the darkness, Marvin Gaye possessed a vocal talent and a quirky, soulful songwriting sensibility that not even the power of cocaine could extinguish.

This was never more evident than on his 1982 album "Midnight Love", which housed “Sexual Healing,” the only Grammy-winning song of his career. (Marvin's only Grammy! A fact that should make the entire Recording Academy hang its head in bitter shame.)

"Midnight Love" is, at its core, a party record. It touts the joys of getting laid, getting high, and… well, that’s about it. After seven tracks soaked in sensuality and narcotics, Marvin makes a turn—however slight—toward redemption. On the album closer “My Love Is Waiting,” he opens with a Jesus-thanking monologue that feels like a spiritual footnote, a last-ditch testament to the inner tug-of-war between righteousness and hedonism that haunted artists like him, Prince, and James Brown their entire lives.

After a long, drug-induced dry spell, Marvin had relocated to Europe in an effort to heal, and the mood on this record reflects that attempt at self-renewal. "Midnight Love" isn’t particularly varied—every track seems built on the same Roland TR-808 drum machine and synth template, the same gear that gave The Isley Brothers their smooth-funk foundation on “Between the Sheets.” But there’s something hypnotic about that sonic consistency. It keeps you swaying.

No, "Midnight Love" isn’t an unequivocal home run. His stab at Caribbean stylings on “Third World Girl” is the album’s weakest track, and the lyrical depth never reaches the philosophical heights of "What’s Going On." But even so, Marvin proves that he can still croon with the best of them on the aching “‘Til Tomorrow,” and “Sexual Healing” remains a blueprint for modern R&B sensuality—slick, minimal, and downright addictive. Album cuts "Turn On Some Music", "Rockin' After Midnight" and "Midnight Lady" are excellent displays of Marvin allowing himself to relax and cut loose a little, something he could not achieve on the bizarre and rigid "Here My Dear".

In all, "Midnight Love" feels like the clouds parting over Marvin’s troubled life, if only briefly. It’s his most enjoyable album since "Let’s Get It On" and serves as a solid, bittersweet epitaph for one of music’s most iconic and tortured geniuses.

69

Freddie Jackson

"Rock Me Tonight"

1985

Nicki Minaj vs. Cardi B? OK. Brandy vs. Monica? Yes. Azealia Banks vs. Iggy Azalea? Definitely. But Freddie vs. Luther? Not sure about that one.

The whole “beef for publicity” gimmick is a relatively new phenomenon, so when Freddie Jackson came out in the mid-’80s, the press tried to stoke a rivalry between him and Luther Vandross. But it didn’t really catch fire. Though both New Yorkers were vying for more or less the same Quiet Storm audience, there seemed to be enough room for both to maneuver without stepping on each other’s soft-soled, velvet loafers.

Both artists released what many consider their most definitive albums in 1985—Freddie’s "Rock Me Tonight" (his debut) and Luther’s "The Night I Fell in Love" (his fourth). The format was nearly identical: a mix of baby-making ballads and mid-tempo grooves, with a cover or two thrown in for good measure. But Freddie saw more crossover success with the now-classic title track “Rock Me Tonight (For Old Times Sake)” and the go-to wedding number “You Are My Lady”—a feat that probably had Luther blowing steam from both ears.

Both singles were strong enough to propel "Rock Me Tonight" to the top of the R&B charts, but the album also contains some underrated gems: “Love Is Just a Touch Away,” “I Wanna Say I Love You,” and “Sing a Song of Love” all keep the energy consistent. Freddie’s vocal approach was an American Idol fever dream: over-exuberant runs, churchy flourishes, and acrobatic melisma that could stretch a two-syllable word into a two-hundred-and-two syllable one.

Vocal subtlety—a tactic Luther mastered to softly court and seduce his listeners—was something Freddie actively avoided. And while his fire-and-brimstone delivery annoyed some, it endeared him to many… at least in the beginning.

The album’s closer, a cover of “Good Morning Heartache,” was probably not the right canvas for Freddie’s Broadway-meets-Baptist style. He seemed to miss the actual heartache right there in the title and instead shot for the rafters like he was auditioning for a gospel revival in Harlem.

Still, with the wildfire success of “Rock Me Tonight,” the fabricated rivalry with Luther was in full swing. It didn’t last long, but Freddie didn’t need it to. He went on to rack up three more chart-topping albums after his debut—proof that even if he wasn’t Luther’s equal in restraint, he was a heavyweight in his own right.

68

Usher

"8701"

2001

Don’t you hate it when record execs blow zillions on marketing trickery to force some no-talent fuck down your throat—while starving you of exposure to truly gifted artists? You know the ones: artists whose popularity has zero correlation to actual musical ability. (Like, how did Britney Spears sell exactly 9 gazillion more records than Joss Stone?)

We old-school music consumers pride ourselves on being savvier than the average bear. We can smell industry manipulation from a mile away and pivot before it even gets close to our wallets. But sometimes, even the best of us miss it—especially when the labels actually get it right and push someone who does have talent, charisma, or, in rare cases, both.

For me, Usher was one of those artists I totally slept on.

I always knew who Usher was, of course—but for a long time, I saw him as just another polished puppet with record execs’ hands halfway up his spine. That impression was cemented when "Confessions" blew up, largely on the back of “Yeah,” one of the most aggravatingly asinine hits in recent memory. (Don’t argue. You know it’s true.)

But here’s what I didn’t fully appreciate: before he took over the world with "Confessions", Usher was already a star with "My Way" and "8701". And for the purposes of this column, I went back and gave "8701" the deep listen it deserves—and was completely floored.

Everything here works—the songwriting, the production, and most importantly, Usher’s first-class vocal performance. When you can assemble an all-star team of early-2000s hitmakers like Jam & Lewis, The Neptunes, and Jermaine Dupri (who admittedly ranks slightly lower on my producer totem pole), it’s almost inevitable that magic will happen.

I could list all the standout tracks, but honestly, it’s easier to point out the two relative duds that close the album: “U-Turn” and “Good Ol’ Ghetto.” And even those would’ve been highlights on a Sisqó or 112 album.

After giving "8701" the proper spin, I feel moved—no, compelled—to use this space to issue a formal apology to Usher Raymond IV. I unfairly lumped him in with the overhyped underachievers of his generation—Robin Thicke, Sisqó, and every other dude who thought a six-pack and falsetto were enough. But "8701" proves that Usher is not only the real deal, he’s been the real deal for a minute.

And now I get it.

67

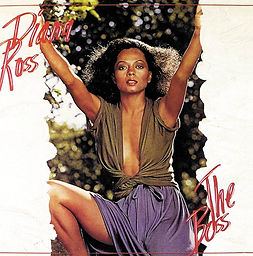

Diana Ross

"The Boss"

1979

I love 1979. Some of my favorite songs by folks like Sylvester, Donna Summer, Michael Jackson, and Sister Sledge hit the charts that year. Even white folks were cooking—Joy Division, Gary Numan, The Cure, and Human League were all forging new sonic terrain, lacing electronic elements into their music that would go on to define the sound of the ‘80s.

But before the synths fully took over, disco was still in its imperial phase—and everybody wanted a piece of the pie. Even Ice Queen Diana Ross. She’d already scored a near-classic disco smash with 1976’s “Love Hangover,” but when that hit faded, so did her commercial shine. For a while, it felt like Miss Ross could do no right. Her post-1976 output flopped with critics and audiences alike. It was Murphy’s Law on wax.

Then came "The Boss".

While it didn’t officially fish her career out of the toilet, "The Boss" did reintroduce us to the spry and confident Ross we’d been waiting so long to hear. Now, Diana has never been a powerhouse vocalist in the vein of Chaka or Patti—but on this 1979 album, she sure tries her damnedest to hold her own alongside those screaming divas. And shocker: she mostly pulls it off.

Truthfully, I’d always avoided Ross’ solo material because I couldn’t stand her voice. That pussycat-with-a-sinus-infection tone—so "Soft Kitty, Sleepy Kitty"—drove me up a wall. Hated it. But on "The Boss", something shifted. She shook herself free of the coy crooning and actually sang. Like, really sang. She attacks the album’s mid-tempo and disco tracks with what I can only call focused ferocity—keeping in mind her vocal limitations, of course.

“No One Gets the Prize,” “It’s My House,” and the title track are absolute gems. But for me, the crown jewel is “Once in the Morning,” especially the final two minutes where Diana lets her voice soar as the song fades out. I don’t need to hear another note from her to declare that performance the most dazzling and satisfying vocal of her long-ass career.

Despite the gold certification, "The Boss" underperformed commercially—and not because of the music. The real saboteur? Motown. The label barely promoted the album, likely due to the ongoing behind-the-scenes drama between Diana and Berry Gordy. Their relationship, both personal and professional, had soured. By this time, she’d scored some major wins—TV specials, hit singles, even an Oscar-nominated film role—but a lot of her lasting reverence still stemmed from her Supremes days. None of her solo studio albums had gone #1, and none were selling Streisand-level numbers.

And yet… "The Boss" should’ve been huge. At least two tracks had the potential to top the charts and pull Diana out of her post-"Mahogany" slump. But Gordy, still salty that Diana had dared to step out on him (allegedly with the long-tongued one from KISS and Eddie Kendrick), let his ego get in the way. Diana, of course, would have the last laugh by dropping her biggest album a year later—her Motown swan song—before inking the most lucrative record deal in history with MCA.That’s all fine and dandy. But for me, her greatest musical achievement will always be this 1979 album.

P.S. Diana Ross turned me gay.

As a small honey chile, I could not stop staring at that album cover. Her flawless face, made up to perfection. That cleavage-baring top. Her toffee-toned skin glowing like a modern-day Nefertiti. And those long, wind-blown tresses cascading past her shoulders—pure glamour. (Inconclusive evidence I wasn’t gay yet: I had no clue that hair had been yanked off a poor Filipina’s head and sewn onto Diana’s.)

Ross was our Black regal beagle—a high priestess of fabulosity—whose image leapt off that jacket, gently took my little boy hand, and whispered in my ear: You, too, can be this fabulous—if you really apply yourself.

That record cover allowed me to embrace fabulosity and gayness. Because let’s face it: straight boys are far too clumsy and corny to ever be truly glam. Like Diana.

And no, this isn’t the first time Diana did this. I’m pretty sure she turned Luther gay, too.

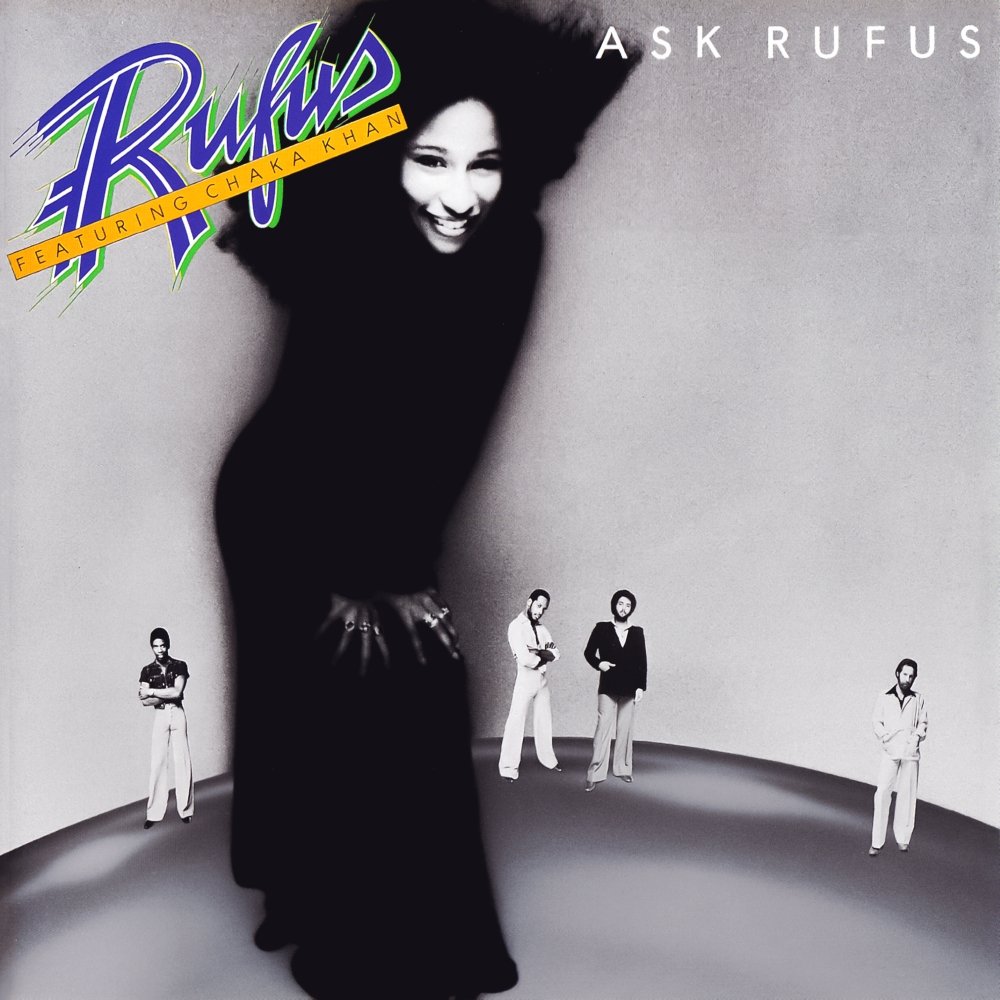

66

Rufus featuring Chaka Khan

"Rufus featuring Chaka Khan"

1975

Chaka Khan was—and still is—a vocal powerhouse. But even powerhouses need a solid foundation to truly shine, and this Rufus featuring Chaka Khan self-titled debut solo album sometimes leaves her grasping for magic that isn’t quite there.

Chaka was known for recording her vocals quickly—one or two takes, in and out—and while that can sometimes yield electrifying results, on this record, the rushed approach is a bit too evident. Her vocals on tracks like “Fool’s Paradise” and “Dance With Me” feel more strained than spirited, like she’s pushing hard to elevate songs that just aren’t worth the effort.

The songwriting here ranges from fair to middling, which meant the heavy lifting fell squarely on Chaka’s shoulders. And while she does inject her signature fire into otherwise ho-hum grooves like “Have A Good Time” and “Fool’s Paradise,” even her powerhouse wails can’t fully mask the thinness of some of the material.

That said, there are standouts. “Sweet Thing,” reportedly written in just ten minutes, is pure magic—and one of Rufus’s most enduring classics. Chaka’s delivery is sublime, balancing vulnerability with strength in a way only she can. “Ooh I Like Your Loving” and “Circles” are also solid entries, and “Little Boy Blue” offers a glimpse of the emotional depth she’d tap into more fully on later albums.

The context behind the album matters. By this point, Chaka’s relationship with Rufus was famously fraught. She was difficult to work with, moody, and notoriously uninvolved in production or rehearsals. A real Lemony Snicket. On top of that, she was a young single mom, juggling motherhood with the demands of constant touring. When it came time to record, there was little room for long songwriting sessions or meticulous vocal retakes—Chaka wanted to get in and get out. And that reality shows in the album’s unevenness.

Still, there’s no denying Khan’s charisma. Even when the material underwhelms, she never does. Her voice cuts through every groove with swagger, sensuality, and soul. While Rufus featuring Chaka Khan went gold and delivered some key highlights, it ultimately falls short of the magic the group conjured on 1974’s "Rufusized." Perhaps sensing this, Rufus and Chaka made the bold (and rare) decision not to rush out another album the next year. Instead, they took two full years to refine their next project—focusing on arrangements, musicianship, and production with renewed intensity.

The result? An absolute classic. But we’ll get to that later in the countdown.

65

Luther Vandross

"Never Too Much"

1981

Life is a cabaret, ole chum! Luther supposedly had something to prove—though you’d never know it listening to his debut. After finagling a Stevie Wonder–style contract that let him produce himself, he financed his demos, bought back the masters of his two earlier albums (released under the name Luther), and entered the game with quite a bit of clout, thanks to glowing endorsements from superstars like Roberta Flack, Nile Rodgers, and David Bowie.

But there’s no sense of pressure or nerves anywhere on "Never Too Much"—especially not on its spectacular title track, which sounds as cool and refreshing as roller skating through the sprays of an open hydrant on a muggy day in The Bronx. Luther was from The Bronx, but you get the feeling he spent a lot of time in Manhattan too—Harlem’s Apollo Theater, the Broadway stages, the cabaret circuit. You can feel those influences all over this record, which seamlessly blends old-school soul sensibilities with a few sly theatrical flourishes—particularly on his definitive reading of Dionne Warwick’s “A House Is Not a Home.” That song is the album’s money shot—an emotional showstopper that unfolds like a one-man play in three acts. And it’s brilliant.

At the time, Luther was already a force in disco, having sung lead or background on dance classics by Bionic Boogie, Change, Chaka Khan, Chic, and more. But for his official debut as a solo artist, he wisely left the pulsing club beats behind. Instead, he opted for a Motown-adjacent sixties soul feel (“Sugar and Spice”), herky-jerky funk (“Don’t You Know That”), and bass-driven post-disco workouts like “She’s a Super Lady” and “I’ve Been Working,” thanks in part to axe man extraordinaire Marcus Miller.

There’s little point in rehashing what we already know about the man with a voice as warm and toasty as a cup of hot cocoa (with marshmallows) on a chilly night in—where else?—The Bronx. Luther’s magic lay in his unhurried delivery. His vocals glowed with a kind of sunshine, like he was smiling the entire time. There was even a bit of playful cheesiness in his lyrics—like when he croons about “riding the winds of a hurricane” back into his lover’s arms—that gave his music a kind of innocence. He sounded like the smooth, charming guy from around the way.

(Of course, we’d learn much later that behind that aw-shucks glow was a ruthless perfectionist and studio tyrant. He could reportedly be a diva from the depths of hell—but damn if the results didn’t justify it.)

Luther rarely missed because he worked a formula that didn’t feel formulaic. He carved out a space in soul music that softened the wildman heat of Teddy Pendergrass, smoothed out the rough edges of Marvin Gaye, and added extra froth to the creaminess of Smokey Robinson. And always—always—a sprinkle of Broadway drama. “A House Is Not a Home” was practically made for the Great White Way, but Luther somehow managed to keep it from going fully over the top. It was a master stroke that would define the rest of his illustrious career.

"Never Too Much" kicked off a run that was nothing short of historic: seven straight No. 1 R&B albums (eight total), nearly every one of his 13 studio albums landing in the Top 5, and even his greatest hits and Christmas collections cracking the Top 2.

It all started right here—with a big heart, a bigger voice, and a debut that sounded like a hug from someone who really gets you. Luther, we never got too much of you.

64

Anita Baker

"Giving You The Best That I Got"

1988

Don’t you just hate it when your BFF—your home slice, your main dude—falls head over heels for someone, and suddenly you’re left sitting there, helplessly watching as this new romance shifts the entire dynamic of your once-solid friendship? That happened to me and my friend Tristan in college. He met this girl—sweet on the outside, nutty as a fruitcake underneath—and slowly but surely, we watched her consume his world. He couldn’t see how being with her was changing him, but the rest of us could.

That’s what "Giving You the Best That I Got" felt like. Between the release of "Rapture" and this, her third album, Anita Baker fell in love—deeply, openly, maybe even a little recklessly—and her fans, like me, could tell. She was still great, still Anita, but she seemed less focused, as if her creative energy was being redirected elsewhere. The music was still top-notch, but some of the urgency—the fire—had cooled.

Now let’s be clear: "Giving You" is a very good album. Like "Rapture", it's very streamlined with no need to skip a single track. But where "Rapture" felt rawer, more organic and emotionally driven, "Giving You" leans into melodic chord structures, big, juicy hooks, and a steadier, more polished sound. It’s cohesive and smooth, but less visceral.

Some fans were caught off guard by the bossa nova-ish rhythm of “Good Enough”—I know I was. It took time to realize that this laid-back groove was actually perfect for Anita’s smoky soprano and her signature phrasing, which always seems to stretch every syllable to the edge of its life.

The strength of this album lies in its evenness. It’s hard to pick a standout among “Lead Me Into Love,” “Good Love,” “Rules,” and “Just Because”—not because they’re forgettable, but because they’re all equally solid. But maybe that’s part of the problem. Nothing knocks you off your feet like “You Bring Me Joy” or “Been So Long.” The songs here satisfy rather than surprise.

Like Tristan—who remained a good friend, just not as present—Anita still delivered the goods. But you can feel where her attention went. She gave what was necessary to keep her fans happy, but the best that she got? That went to her man.

And honestly, that’s not a bad thing. Sharon Bryant had already advised us that when love calls, you'd better answer. But let’s tell the truth: this album is less a love letter to us and more a diary entry from someone deeply invested in someone else. Beautiful? Yes. Relatable? Absolutely. But somewhere deep inside, you can’t help but feel like Anita was saving a little bit more for Walter than she was for us, her diehard fans. A big mistake on your part, 'Nita, because Walter is now long gone and we're still here for you...and we ain't goin' nowhere!

63

Prince & the Revolution

"Parade"

1986

Very rarely does an album cover so much ground in so little time without stopping to catch its breath. And I’m not talking about the Gloria Gaynor/Donna Summer-style BPM segues that keep the groove going. I mean actual musical terrain—the Beatlesque whimsy of “Christopher Tracy’s Parade,” the stripped-down funk of “New Position,” the baroque soul of “Under the Cherry Moon,” the cinematic instrumental sweep of “Venus de Milo,” and the chic, French-café charm of “Girls and Boys”—all somehow living harmoniously on the same record. That this dazzling, disorienting swirl feels completely coherent is a miracle in itself. Credit Prince, of course, but also the brilliant sequencing and mixing that turn what could’ve been a mess into a masterpiece.

Side two slows the tempo but never lets up on quality, housing two of Prince’s most distinct and contrasting songs of the ’80s: the lush, expansive “Mountains” and the skeletal, twitchy “Kiss.” These two tracks, more than any others, highlight the indispensable and often uncredited contributions of Wendy & Lisa (on “Mountains”) and the band Mazarati (on “Kiss”). “Parade” closes with “Sometimes It Snows in April,” a song that didn’t fully reveal itself until Prince’s death. With lyrics about death, rebirth, and bittersweet memory, it now reads like a quiet, accidental epitaph.

Ironically, "Parade" outshines the film ("Under the Cherry Moon") it was designed to support. The album plays like a whirlwind art installation—part cabaret, part funk revue, part French New Wave soundtrack. Only years later did we learn how much Wendy & Lisa influenced the dreamy, rococo textures of the album’s best moments. Their presence deepens the palette, coloring Prince’s compositions with complex harmonies and emotional nuance.

What other ’80s album (aside from maybe something by Frank Zappa) moves so quickly through so many genres without feeling disjointed? One moment you’re sipping coffee at a French café, the next you’re sweating it out on a Detroit dance floor. That’s the magic trick Prince pulls off here. "Parade" may be the natural evolution of "Around the World in a Day", but it’s also so much more than that—it’s tighter, bolder, braver and, most importantly, doesn't stink.

Unsurprisingly, "Parade" and its equally ambitious follow-up, "Sign o’ the Times", were better received in Europe, where audiences were more attuned to experimentation and theatricality. American listeners, still drunk on the rock-drama of "Purple Rain", didn’t know what to make of all the strings and surrealism. Their loss. This is one of Prince’s finest works with The Revolution—an album that balances wit, sensuality, sophistication, and strangeness in a way no one else could. It’s the sound of an artist at the absolute height of his inventiveness, throwing glitter at the rules and watching it all fall beautifully out of order.

62

Earth, Wind & Fire

"Gratitude"

1975

This is the only live album featured in this entire tome—and for good reason. I generally don’t go in for live albums. Too often, they tinker with the magic of the originals, dragging out arrangements or indulging in crowd-pleasing tricks that distract more than they elevate. But "Gratitude" is different. It had a distinct advantage with me: I was four or five years old when I first heard it, and it was my earliest substantial exposure to Earth, Wind & Fire’s music. This double album was a permanent fixture in our home, and for me, the live versions of songs like “Devotion” and “Reasons” were the real versions. To this day, the studio cut of “Devotion” feels strangely subdued next to Philip Bailey’s live performance, which is nothing short of transcendent. Bailey is the star of "Gratitude", floating over the band’s tight arrangements with falsetto high notes that kiss the heavens square on the mouth.

And while the live material takes up most of the album, the five studio tracks that close Gratitude are just as essential. The title track is a meditative groove laced with serenity. Skip Scarborough’s “Can’t Hide Love” remains one of the most gorgeously constructed soul ballads ever written. And “Sunshine”? That’s one of Earth, Wind & Fire’s finest compositions—radiant, hopeful, perfectly balanced between gospel uplift and jazz sophistication.

I heard someone say on TV recently that great music only gets better with time. That rings true here. "Gratitude" hasn’t just aged well—it has deepened. The joy, reverence, and musicianship packed into these grooves sound even more vital now than they did then. And it’s about time Maurice White got his proper due. We talk about Quincy, we praise Stevie, we rightly deify Prince and Marvin—but Maurice White belongs in that same upper tier. In the ’70s, going gold was a major accomplishment for any Black artist. Earth, Wind & Fire were going multi-platinum routinely. "Gratitude" went triple platinum, which was—and still is—an astonishing feat for a live album, let alone one by a Black band. Kudos!

61

Kashif

"Kashif"

1983

Ever watch an award show where some artist grabs the mic, hoists the trophy, and immediately thanks God for blessing them? Or a sports game where, after a touchdown or a goal, a player points skyward in reverence, as if Jesus personally sprinkled them with elite athleticism? It can feel… unfair, right? Like God’s up there cherry-picking who gets divine favor, while the rest of us are left to grind three times as hard for a fraction of the recognition. If that feels harsh, imagine how it must have been for Kashif—one of the most innovative, forward-thinking musicians and quietly masterful producers in R&B. When he died of a massive heart attack in September 2016, the world barely flinched. Aside from a Wikipedia update and a few tribute posts, the axis of pop culture kept spinning as if Kashif had never existed.

And that’s tragic. Because not only was Kashif an extraordinary producer, he was the architect behind one of the most overlooked and most criminally underrated debut albums in all of R&B. "Kashif" (1983) was a game-changer. Half the songs are bona fide Quiet Storm classics before Quiet Storm had fully crystallized as a genre. Tracks like “Stone Love,” “Help Yourself to My Love,” and “Say Something Love” have aged like the finest vintage wine—but only “I Just Gotta Have You (Lover Turn Me On)” cracked the R&B Top 20 (peaking at #5). Why didn’t this album explode?

It’s not like Kashif was an industry unknown. By ’83, he had already produced stone-cold hits for Evelyn “Champagne” King (“I’m in Love”), Melba Moore (“Take My Love”), and Howard Johnson (“So Fine”). And let’s not pretend that Arista Records was too preoccupied with other Black artists at the time—Aretha and Dionne weren’t exactly dominating the charts, and Whitney Houston’s debut was still two years away.

So what gives? Maybe it’s simple: God didn’t set aside any special blessings for Kashif. He didn’t get the magic wand treatment. Instead, he had to work—brilliantly, consistently, and without fanfare. He had to make art without the halo, the hype, or the Grammy. "Kashif" is one of the most ambitious, lush, and sonically progressive albums of 1983, and its relative commercial failure is a disheartening reminder of how often genius goes unacknowledged when it’s not wrapped in divine narrative or marketing dollars.

It’s easy to celebrate the icons we’re told to worship. It’s harder to pay tribute to the ones who paved the way and never got the flowers. Kashif never got to point both index fingers toward the sky in a Grammy acceptance speech. But maybe that’s exactly why this album still feels so pure, so righteous, and so worthy of rediscovery. It was never about the spotlight—it was about the music. And the music is eternal.

60

Dawn Richard

"Blackheart"

2015

I’m not even gonna front—for the longest time, I thought Danity Kane was the title of a Janet Jackson album. As a permanent resident of Colombia since 2000 and a non-participant in the social media matrix, I missed out on most of the reality TV hysteria that swept through Black culture in the 2000s, save for "Flavor of Love" and "I Love New York", which were entertaining as hell. Beyond the "Chappelle’s Show" spoof, I hadn’t really heard of the "Making the Band" series. And even if I had caught a Danity Kane track back then, I would never have connected it to that Puffy-fueled spectacle.

So when I stumbled across Dawn Richard in 2023, I approached her music with no baggage, no bias. I didn’t associate her with girl groups or reality show antics. I just pressed play on "Blackheart"—and what I heard stopped me cold.

Though technically her third studio album, "Blackheart", like her previous work, was partially self-financed—crowdfunded on Kickstarter, supported by whatever coin she scraped together from the Danity Kane reunion tour and whatever loose change she fished out of the couch cushions. But what she produced doesn’t sound like something cobbled together. It’s a fully realized, atmospheric, genre-blurring record. It’s cold and futuristic in places, tender and human in others. Above all, it’s an album that sounds intentional, bold, and brilliant.

It’s impossible not to compare "Blackheart" to Beyoncé’s "Beyoncé" (2013) or the ambient, moody soundscapes of artists like H.E.R. or Billie Eilish. Beyoncé’s self-titled album—and "Renaissance", for that matter—are both creative high points in her discography. But there is nothing on either that dares to venture as far out into space as "Blackheart". This is a concept album in the truest sense, and like "Paul’s Boutique" or "Sign O’ the Times", breaking it down track by track would be missing the point. (Okay, spoiler: The "Blackheart" tracks “Blow” and “Billie Jean” are not remakes.)

"Blackheart" is like a mysterious package left on your doorstep by the coolest alien on Jupiter. I’m sure there’s a conceptual through-line, but frankly, I don’t care—I’m just here for the production, the turns, the unexpected texture of it all. Yes, Richard’s vocals are run through Auto-Tune, but on a record this otherworldly, it works. Her voice becomes an instrument—processed, modulated, floating in and out of digital mist. It’s all part of the aesthetic.

After falling in love with this album, I went back and listened to the rest of her “heart” trilogy—"Goldenheart" (2013), and "RedemptionHeart" (2016)—and was floored by how consistently excellent they are. This is the direction Black music should have gone. Parliament-Funkadelic and The System cracked the door. Janelle Monáe and Kaytranada pushed it open. And Dawn Richard is running through it like the anchor leg in a cosmic relay race.

I see she’s kept releasing critically acclaimed projects as recently as 2022. But because I’m not on Black Twitter or NiggaTok, I genuinely don’t know if people are talking about her, or if she still has to panhandle for studio time on an L.A. offramp. If she isn’t financially sustaining herself off downloads and performances by now, then something is deeply wrong with this goddamn world.

It also seems like her stint on Making the Band and her association with Bad Boy has worked against her. That kind of mainstream exposure can sometimes vacuum the legitimacy out of your artistic ambitions. But Dawn Richard is no earthbound pop-tart like Nicole Scherzinger or Scary Spice. She didn’t take the Booty-Out-Titties-First route to musical success. Like Missy Elliott before her, she was brave enough to go left—making experimental, genre-blurring, deeply personal music that deserves far more recognition.

If you’re out there reading this, Dawn: Keep doing yo' thing, baby girl. Some of us see you. Some of us hear you. And we’re listening.

100

Kaytranada

"99.9%"

2016

I’m not sure when Canada became a sovereign republic, but ever since, it’s mostly just sat on America’s head like a big, boring wig. Besides Joni Mitchell and Michael J. Fox, Canada’s cultural exports have often been more cringe than credible—think Michael Bublé, Cree Summer, or Loverboy. But in the late ’90s and 2000s, something shifted. Canada started redeeming itself with actual talent like Drake, Deborah Cox , and Nelly Furtado… okay, maybe not Nelly.

Leading that renaissance is Kaytranada, the Haitian-Canadian producer who dropped one of the most enjoyable Black pop albums of the 2010s with “99.9%” in 2016. At nearly 60 minutes long and featuring Anderson .Paak, Vic Mensa, Craig David, Syd tha Kid and more, the album is a genre-hopping, no-skips-needed joyride. Kaytranada plays with house, funk, hip-hop, and R&B like he’s jumping through a sonic hopscotch board—effortlessly and joyfully.

There’s a thread of solitude running through these tracks, a kind of moody introspection that’s common in electronic music—but Kaytranada manages to make it shimmer. Every track is dialed in to the right length, energy, and vibe. Some have rapping, some have vocals, some are instrumental, and somehow it all fits.

Dear Canada: More Kaytranada, please. And while you’re at it, come get yo' boy Justin Bieber.

99

Freddie Jackson

"Do Me Again"

1993

“Do Me Again” was Freddie Jackson’s fourth and final number one album—and, for me, a much-needed rebound from his uninspired 1988 release "Don’t Let Love Slip Away". By this point in his career, Freddie had been dancing dangerously close to redundancy, clinging to the same velvety ballad formula that made him a star but left him sounding increasingly stale. That ’88 album felt like someone just erased his vocals from his earlier hits and had him re-sing new lyrics over the same ole tracks.

Meanwhile, a pack of bedroom crooners—Glenn Jones, Phil Perry, Eugene Wilde—were gunning for Luther’s Pillow Talk Crown, just like Freddie. The air was crowded, and Freddie’s brand of Cognac soul was beginning to sound like background music at a neighborhood Applebee's.

But "Do Me Again" came along and showed that Freddie still had some signs of life. The album didn’t reinvent Freddie, but it introduced just enough variation in production and tone to keep things interesting. Yes, there are stumbles (“It Takes Two” and “I Can’t Take It” don’t stick the landing), but this time around, Freddie actually sounds like he’s enjoying himself and not just focusing on melisma-ing the phuck out of the room.

Standouts like “Love Me Down,” “Don’t It Feel Good,” the title track, and especially “Main Course” show a Freddie who’s a little looser, more playful, and finally allowing his vocals to serve the songs—not overpower them. This isn’t his most iconic album, but track for track, "Do Me Again" might be his most satisfying.

Of course, the clock was ticking. This was the last moment before New Jack Swing and the Let-Me-Pop-Yo'-Coochie era of Jodeci, R. Kelly, and Blackstreet washed Freddie (and most of the secondary crooners) out to sea. But for a brief moment in 1990, he still had enough heat to keep the grown folks dancing slow at Black Night at Bennigan's.

98

Sly & the Family Stone

"Fresh"

1973

Between 1968 and 1973, Sly and the Family Stone released six albums, and four of them are among the most consequential recordings in all of popular music. Songs like “Stand!,” “Everyday People,” and stand-alone singles like “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” are pure genius. But for me, “Family Affair” stands as Sly’s most definitive statement—his most iconic and groundbreaking song. It changed music forever. There would be no Prince without Sly.

With "Fresh", Sly tries to recapture the stripped-down brilliance of “Family Affair,” leaning hard into the skeletal rhythms of the Maestro Rhythm King MRK-2 drum machine and a looser, more improvisational feel. Lightning may not strike twice, but tracks like “If You Want Me to Stay,” “Frisky,” and “If It Were Left Up to Me” are funky enough to keep things moving.

Still, not every track lands. Songs like “Thankful N’ Thoughtful” sound like they’re cut from the same cloth as the highlights but fail to stand apart. And while I’m still not sure what to make of the Doris Day remake “Qué Será Será,” "Fresh" ultimately feels like a creative recalibration—a tighter, more focused follow-up to the murky and divisive "There’s a Riot Goin’ On".

For newcomers, your best entry point is the excellent 2004 Anthology collection, but for those already initiated, "Fresh" is a fascinating, if uneven, chapter in the story of one of pop’s true innovators. May Sly rest in everlasting power.

97

Isaac Hayes

"Joy"

1973

Do you like it thick or do you like it long? On "Joy", Isaac Hayes gives you generous doses of both, so you don’t have to choose. With 1969’s "Hot Buttered Soul", Hayes flipped the script on Black music with psychedelic, masterfully orchestrated soul-funk that redefined what soul could be—laying the groundwork for Marvin, Stevie, and Curtis to follow. By 1973, he had moved from being Stax Records’ star songwriter (alongside David Porter) to one of the biggest icons in soul music. His previous four albums all hit number one, each more experimental than the last.

"Joy", however, plays things a bit straighter. Gone are the extended covers and lush orchestrations—this time, Hayes leans into more direct, unfussy R&B. The nearly 16-minute title track is classic Isaac: seductive, slow-burning, and heavy on vibe. But elsewhere, signs of fatigue start to show. After dropping seven albums in under five years, Hayes' robust baritone sounds particularly worn on “A Man Will Be a Man” and “The Feeling Keeps on Coming.” “I Love You That’s All” is more a kooky, meandering spoken-word skit than an actual song.

That said, “I’m Gonna Make It (Without You)” is a standout. It clocks in at over 11 minutes but earns every second, thanks largely to the soulful backup singers who keep it from drifting too far into syrupy territory.

"Joy" might not hit the heights of "Hot Buttered Soul" or "Black Moses", but for those nights that require a heapin' helpin' of slow jams and candlelight, this album more than holds its own. If mekkin’ luv is on your agenda, this one’ll help you get the job done.

96

Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings

"Give The People What They Want"

2014

Sharon Jones had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer a year before "Give the People What They Want" was released, but you’d never know it from the way the music slaps. This album is bursting with life—Jones sounds vibrant, playful, and as powerful as ever, especially on tracks like the giddy “Stranger to My Happiness.”

While it may not include a showstopper like “How Do I Let a Good Man Down,” this is one of the strongest and most consistent sets Sharon and the Dap-Kings ever put down. “Now I See,” a song about betrayal, still radiates with a joyful defiance that Jones was known for. The James Brown influence remains obvious, but there’s also plenty of Gladys Knight in Jones’ delivery—soulful, grounded, and emotionally sharp. There is no skipping forward required the minute you program "Give the People What They Want" into your phone, something you probably can't say about 99% of the albums that came out in 2014.

I didn’t learn about Jones’ cancer diagnosis until after I’d heard the album, and unlike Bowie’s "Blackstar", which hits you like a epitaph even if you didn't know about Bowie's terminal condition beforehand, "Give the People" doesn’t sound like a swan song. It’s filled with fire, joy, and optimism. In hindsight, that resilience makes "Give the People What They Want" even more powerful—and for me, it stands as one of the best records in her catalog.

95

Van Hunt

"The Fun Rises, The Fun Sets"

2015

I grew up around white people and learned a lot from them. One thing that always unsettled me—even back then—was their uncanny ability to create and live in an alternate universe. And it often goes unchallenged. This was long before the QAnon circus or the “it happened/didn’t happen” chaos of January 6. We’ve seen this before—in Holocaust denial, in school textbooks that rebrand chattel slavery as “imported labor” and so on and so forth.

White folks get it wrong, though. As with so many other things, they use alternate realities as a vehicle for hate and delusion rather than to dream up utopias—like world peace or, I don’t know, multiple orgasms for men. Meanwhile, Van Hunt is out here crafting his own alternative universe—one built on music, ideas, and radical imagination. His is a world where funk, new wave, rock, punk, soul, and R&B all live harmoniously on the same block creating an interesting musical hybrid unapologetically delivered by a Black man from Ohio.

In this universe, Frank Zappa, Prince, Sly Stone, (early) Joe Jackson, Lenny Kravitz, and even a dash of Missing Persons all sit around the same dinner table, making weird, beautiful noise together. Van Hunt is the observer, the narrator, the shape-shifter. He sings about love, gender, consumerism, misfits, and sex with a sly smirk and an eyebrow raised.

Truthfully, Black listeners often haven’t been given the opportunity—or permission—to engage with music this complex or so way out in left field. And that’s not on us. The record industry made sure that what we heard was either party music or baby-making music. Anything outside of those two boxes were labeled “not commercially viable for the Blacks.” The industry didn’t grow by trusting consumer free will—it grew by repeating the same curated playlists until we all bought in.

Van Hunt has never made those playlists, and "The Fun Rises, The Fun Sets" is exactly why. It’s whimsical, wacky, fearless, genreless, and messy—in the best way. It demands attention. It resists categorization. It’s not for everyone, but it should be. Because what Van Hunt gives us is freedom—musical, cultural, and imaginative. But you’ve got to do the work to live in his universe. And most people simply won’t invest the time and effort to do so. Especially "the Blacks".

94

Cameo

"Single Life"

1985

“I don’t wanna get too serious / I just like having fun.”

On the surface, that lyric may seem tone-deaf, especially at a time when the AIDS epidemic was ravaging minority communities and a storm of conservatism loomed over pop culture. But in many ways, it reflects a deeper, long-standing reluctance within the Black community to confront anything that might challenge the rigid machismo we cling to—an emotional armor that’s kept too many of us stuck in the Mental Stone Age.

Larry Blackmon wasn’t exactly leading a liberation movement, but he was definitely doing something. By the time "Single Life" dropped, he was beginning to explore his “dick out” era—styling himself in a red leather codpiece, demanding attention, and daring you to question what you were looking at. This was post-"She’s Strange", and Cameo had fully transitioned into a synth-funk juggernaut on the Black charts. But now, with "Single Life", they added more humor, more swagger, and a sharper sense of their own absurdity.

In the music video for the title track, Blackmon wears a wedding dress before ripping it off to reveal leather gear and his signature flat-top, balancing camp and cockiness in a way that—whether intentional or not—pushed against traditional ideas of masculinity. He was never too far from queer aesthetics, but like many of his contemporaries, he wielded those aesthetics without ever confronting them directly. This was the ‘80s, after all. Everyone was a little gay--even the niggaz--but no one was talking about it like, say, Prince was.

Musically, "Single Life" is a strong, genre-blurring affair. Jazz, reggae, funk, soul, and electro all show up to the party. It might be Cameo’s most cohesive and confident album, actually. Tracks like “Attack Me With Your Love” and “Single Life” are funky, and laced with enough innuendo to make a church lady blush. And let’s be honest: this is probably the only time anyone in the history of recorded music has begged to be “bushwhacked” with someone’s love. You can’t make that up.

If "She’s Strange" was the pivot, "Single Life" was the arrival—Cameo fully embracing their weirdness, sexuality, and sense of play while still delivering stone-cold funk. Cameo is one of my very favorite bands and back in the 80s, no one else was doing it quite like them and no one else ever would.

93

The Internet

"Ego Death"

2015

From Joan Armatrading to Meshell Ndegeocello to Brittany Howard and on down the line, I’ve always had a soft place in my heart for Black lesbian artists. Unabashedly sentimental and strikingly frank, they tend to carve out a unique niche—often by deliberately sidestepping musical and cultural trends rather than chasing them. "Ego Death", The Internet’s third and highest-charting album, fits squarely into that tradition.

At the center is Syd (formerly Sydney) Bennett, whose creamy, effortlessly smooth vocals give the album its emotional core. Listening to "Ego Death" feels like cruising down the Pacific Coast Highway with the top down on a warm day—breezy, easy, and sun-soaked. The lyrics are sometimes brazen and narcissistic, but never come off as hostile. They’re always softened by the unmistakable hint of vulnerability and honest insecurity that Syd weaves into each track.

While Syd handles most of the vocals, "Ego Death" is clearly a collective effort. The musical contributions from the band are precise and thoughtful, especially from standout bassist, co-producer and Funny Black galore Steve Lacy, whose fingerprints are all over the record’s groove-heavy feel. Kaytranada—the ever-inventive Haitian-Canadian—drops in to produce the album’s standout track, “Girl,” a silky slow-burn that glides along Lacy’s deep bass line like a hovercraft over a lake of honey.

"Ego Death" feels like the kind of record I once hoped Lucy Pearl might make: loose but airtight, spontaneous yet methodical, sexy without trying too hard. That kind of balance is only achieved by serious musicians who trust each other—and it shows. There’s nothing manufactured about "Ego Death". It just flows from start to satisfying finish.

92

Donna Summer

"Once Upon A Time"

1977

This is where the legend of Donna Summer really starts to come together. By this point, she had shed much of the sex-kitten purr that defined her earlier work and began to plant herself firmly at the center of dance music, not merely as a seductive figure but as a fully commanding vocalist. Her singing on "Once Upon a Time" is more forceful, more expressive, and layered with a sense of purpose that elevates the entire project higher than previous records.

A conceptual double album sung from the perspective of Cinderella, "Once Upon a Time" finds Donna diving into narrative songwriting with surprising depth and confidence. But it’s Side 2—the electronic disco suite—that feels like the beating heart of the album. “Now I Need You” and "Midnight Shift" aren’t just standouts—they’re career highlights. Cold and creepy, yet soft and vulnerable, these two songs in particular remain two of my all-time favorite Donna deep cuts.

As with her earlier albums, the songs are intricately mixed together, flowing seamlessly from one to the next in a continuous beat that make the album feel like a living, breathing performance rather than a collection of tracks. The storytelling, the production (once again courtesy of Giorgio Moroder and Pete Bellotte), and Donna’s ascending vocal power all coalesce here in a way that makes "Once Upon a Time" a pivotal and sometimes underrated cornerstone in her discography. It was also the first in three consecutive double-albums to hit number one on the Billboard Hot 100, and a sign of much bigger things to come for Donna.

91

Karyn White

"Make Him Do Right"

1994

You’ve been making half-court shots, tomahawk dunks, and 360-degree turnaround layups all afternoon. You’ve been nothing less than unstoppable. Dripping with sweat and out of breath, you turn around—only to realize no one saw it. Not a single soul. You didn’t even set up your iPhone to document your Allen Iverson-inspired greatness. Just like that, your brilliance disappears into the ether like a tree falling in an empty forest. That’s exactly how I feel about "Make Him Do Right", Karyn White’s most overlooked and misunderstood album.

The first mistake was leading with “Hungah”—the orthographically challenged and sonically underwhelming album opener. It felt like a discount version of Janet Jackson’s “That’s the Way Love Goes” and set the tone for an album that, at first listen, felt patchy and directionless. The first two-thirds of the record often have you hovering near the fast-forward button, which is a shame, because the final third is where the gold nuggets are buried. And in hindsight, that’s where we should’ve started all along.

Beginning with “Simple Pleasures,” Jam & Lewis finally stop the genre gymnastics and lock into what Karyn had quietly become: a grown-ass A/C balladeer. Despite debuting with uptempo smashes like “The Way You Love Me” and “Facts of Love,” the long-term impact of “Superwoman” and the lukewarm reception of her dance-heavy sophomore album had clearly repositioned Karyn as a midtempo and ballad artist. The final four songs here are among the strongest in her career. Karyn’s voice has never been about vocal pyrotechnics, but she has an emotive clarity that makes tracks like “Thinkin’ ’Bout Love” and “One Minute” hit just right—sincere, tender, and believable.

But getting to those tracks means wading through some missteps. Attempts to recreate the empowering tone of “Superwoman” backfire on “I’d Rather Be Alone” and the title track “Make Him Do Right”—both missing the nuance and conviction of her earlier hit, and landing more like forced sequels than fresh statements.

Now let’s talk about the real crime: the fact that “Can I Stay with You” wasn’t the lead single. This Babyface-produced gem is a between-the-legs, triple-somersault jam—an elegant, yearning ballad that should’ve been a signature moment for Karyn. Instead, it was buried as the second single and peaked at only No. 10, partly due to the dud that was “Hungah.” “Here Comes the Pain Again” is another forgotten treasure—an emotional gut-punch that hit hard when I was younger and still gets to me today.

It’s frustrating that this album went mostly ignored, because despite its uneven front half, "Make Him Do Right" is Karyn White’s most solid and emotionally cohesive project. If you make it past the fluff and find your way to the back stretch, you’ll discover an album full of genuine feeling, understated craftsmanship, and some of the most quietly powerful songs in her catalog. Sometimes the best games don’t get televised—but that doesn’t make them any less legendary.

90

Maysa

"Maysa"

1995

Before striking out on her own, Maysa lent her smoky, velvety vocals to British jazz-fusion outfit Incognito, helping to define their sleek, soulful sound. With her 1995 self-titled solo debut, she stepped into the spotlight—and while it never got the recognition it deserved, the album is far from a misfire.

On paper, Maysa had the ingredients for success: contributions from powerhouse vocalists like Sharon Bryant, Angie Stone, and Siedah Garrett, with production by hitmakers Robbie Nevil and Barry Eastmond. Expectations were clearly high. But Maysa was signed to a fledgling label with a shoestring promotional budget, and as a result, the album never really had a fighting chance on the charts.

But commercial success and artistic value don’t always go hand in hand. Au contraire, mon frère. While the album does open with a few sluggish, uninspired R&B numbers that don’t quite match Maysa’s potential, things begin to shift around track six. That’s when the magic starts.

“J.F.S.” kicks off a remarkable back stretch that transforms the album into something memorable. From there, songs like “Alone at Last,” “Peace of Mind,” and the stunning “Rain Drops” show off Maysa’s ability to channel deep emotion with grace and subtlety. “Rain Drops,” in particular, is hauntingly beautiful—a melancholic masterpiece that’s brought real tears to my eyes on more than one occasion. The album ends on a high note with "Goodbye", the title sadly serving as a reference to Maysa's career expectations.

Though "Maysa" didn’t get the attention it warranted at the time, it stands as a quiet triumph of mood, melody, and vocal warmth. And happily, this debut was just the beginning. Maysa has continued releasing music well into the 2010s, with her 2015 album Back 2 Love even cracking the Top 10 on the R&B charts. She may not have had a blockbuster start, but she carved out a long, soulful career on her own terms.

Kudos, Maysa. You deserved more flowers then—but I'm giving them to you now.

89

Aretha Franklin

"Sparkle" (Original Soundtrack)

1976

After co-reigning with James Brown over the charts and Black entertainment since 1967, Aretha Franklin entered the 1970s on a high. She was at the peak of her powers—crossing over into pop, racking up R&B hits, and even conquering gospel with "Amazing Grace" in 1972, which became the biggest commercial success of her career.

But then… the wheels began to wobble.