Black Gaddy’s Top Singles

Since I’m not a music critic, I don’t have to play nice or spread the love just to look balanced. If this list is heavy on a few favorite artists, that’s because—well—I actually like their music more than most. When you’ve got favorites, you tend to ride with them, track after track. You might even see a couple songs by the same artist sitting back-to-back. That’s not favoritism—that’s just mathematics at work. I used a numerical ranking system to put this thing together, and sometimes the numbers clump. If that happened, I just left it that way because I don't have time to argue with math.

Let’s be clear: these lists aren’t comprehensive, and they definitely aren’t based on deep research. They’re just collections of songs your Black Gaddy happens to like. So if you see an overabundance of certain artists and a complete absence of others, that’s why. Personal taste doesn’t always strive for balance.

For the “Black” lists, the artists are, in fact, Black—or at least juuuuuuust Black enough to scrape by and qualify. (Looking at you, Stacy Lattisaw.) Meanwhile, the “White” lists are for white artists… and for those who, while racially ambiguous, still land on the whiter end of the pop spectrum. So yes, folks like Teena Marie, K.C. and the Sunshine Band, The Jets, Exposé, Lisa Lisa, and Gloria Estefan—y’all are on the white list. (I suffered many a sleepless night deciding on where to put Mariah Carey. But at the end of the day, she landed with the Blacks, mainly because of that "Butterfly" album and the fact that she got a Black baby daddy. Again, no rocket science going on around here, folks.

Why do I need separate lists for Black and white artists?

Because "you gotta keep ‘em separated", as the song goes. I don’t mix Black and white artists because we make music under entirely different circumstances—and often for completely different reasons.

White folks might revere Van Morrison for his whatchamacallit or worship The Beach Boys for their… whatever it is they love about The Beach Boys. But we don’t celebrate Teddy Pendergrass or Minnie Riperton for those same reasons. And they weren’t making music for people trying to get lost in the studio ingenuity of Pink Floyd. Putting all of these artists on the same list feels like comparing rutabagas and watermelons—different roots, different flavors, different purposes.

The full list of Black artist singles originally has 1,060 entries, with a cap of 10 songs per artist. But I couldn’t include them all—because my webmaster in India told me it would cost an extra $400 to make it happen. And since I earn Colombian pesos, I wasn’t tryna hear it. So I trimmed it down to 500 entries, which meant cutting out a lot of minor artists. Still, I made an effort to spread the love and include a solid mix of one-hit wonders and underrated acts who never seem to get Billboard love—names like R.J.’s Latest Arrival, Princess, and Loleatta Holloway.

Also, I make no differentiation between Soul and Black Disco as they come from the same place. However, somewhere on this site, there is a separate list for Disco that brings together artists from all racial backgrounds onto one list. If you don't see it yet, it's on the way.

Also, I just can’t with the Rolling Stone magazine lists. Half of them are basically The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and the gawd-awful Bob Dylan on repeat. It’s like they think music history starts and ends with "Abbey Road" and nasal poetry. (I actually like "Abbey Road", but I'm not tryna to take it under the bleachers and get it pregnant.)

And when white critics do try to talk about Black music, they usually get it wrong. Anyone who truly digs Rick James knows “Super Freak” isn’t even close to his best track—just like no real Bruce Springsteen fan would claim “Born in the U.S.A.” is the Boss at his peak, though this is the song we most recognize by him. But songs like "Super Freak" are the ones that always show up on their lists, because the folks making them only explore as deep as what’s been spoon-fed to them by mainstream radio. They don’t know what’s underneath the surface—and frankly, they’ve never bothered to look.

There’s no way the Rolling Stone writers could ever fully grasp that, as massive as “Billie Jean” was in the post-disco era, songs like "Cutie Pie” by One Way or “Atomic Dog” by George Clinton hit just as hard—if not harder—in our communities. Those records weren’t just songs; they were soundtracks to house parties, skating rinks, cookouts, and late-night slow rolls. But because they didn’t cross over to mainstream white radio—or didn’t come with a groundbreaking music video—they get passed over like they never happened. You had to be there. And clearly, they weren’t.

Black Daddy Music is my attempt to recognize, recapture and keep alive the music that made us who we are today without the necessity to filter our music through mainstream sensibilities.

So, if you want to take this ride down memory lane with me, take heed to the immortal words of D-Train and "Keep On" reading.

300

The Bangles

"Hazy Shade of Winter"

1987

Prince wanted to fuck The Bangles’ doe-eyed frontwoman Susanna Hoffs, so he dove into his vault and pulled out “Manic Monday,” a track originally meant for Vanity- or Apollonia 6 (honestly, who can keep track at this point?). He gave it to The Bangles, reportedly spending much of the studio time silently staring at Hoffs while barely acknowledging the uglier chicks in the band. The romantic connection never materialized, but the song blew up, launching The Bangles into the pop stratosphere.

With their newfound fame, the group had the clout to take bigger creative swings—like their blistering cover of Simon & Garfunkel’s “Hazy Shade of Winter,” featured in the coke-drenched ‘80s classic movie "Less Than Zero". This version, with its driving guitars and tight four-part harmonies, let every band member shine instead of leaving Hoffs to carry the whole thing. It’s a ferocious improvement over the folky original and one of the key tracks that established The Bangles as a legitimate rock band—not just a pop girl group.

299

Annie Lennox

"Walking On Broken Glass'

1992

We all loved the Eurythmics, but there was always a question mark around whether their androgynous and undeniably talented lead singer, Annie Lennox, could make it on her own. Truth be told, the group had started faltering in the U.S. once they shifted away from the icy, electronic sound that made them stars. Still, it was clear Lennox had the pipes—and the vision—to pursue something more soulful. Her debut solo album was a global smash and delivered a handful of excellent singles, including the orchestral-dance gem “Walking on Broken Glass.” Lennox would go on to become one of the most respected and successful female artists to ever emerge from the U.K.—a well-earned accolade. And yes, we’ll be seeing her again on this countdown.

298

U2

"In God's Country"

1987

U2’s "The Joshua Tree" looms large in the soundtrack of my life. It remains one of my favorite records, and a big reason for that is “In God’s Country.” The Edge’s slicing, crystalline guitar work cuts through the track like desert sunlight, providing a perfect backdrop for Bono’s strident, haunted vocals. The album, famously inspired by the contradictions of America—its beauty and its brutality—hits especially hard when I’m riding my bike through the wide, empty stretches of the Arizona desert. Out there, “In God’s Country” loops in my head like a hymn to both hope and disillusionment. Back then, I loved U2 fiercely. These days… not so much.

297

The Jets

"You Got It All"

1985

“You Got It All” has a surprisingly layered backstory. Co-produced by David Z—older brother of Bobby Z from Prince’s Revolution—the track was written by Rupert Holmes, best known (and sometimes mocked) for that frothy yacht-pop staple, “Escape (The Piña Colada Song).” Holmes originally wrote “You Got It All” for his 10-year-old daughter, who tragically passed away before the song was ever recorded. The Jets picked it up in 1986, with 12-year-old Elizabeth Wolfgramm taking lead vocals. Too young to grasp the song’s romantic overtones, she was reportedly told to imagine singing it to a puppy.

We were in high school when the track came out, and of course we found juvenile ways to misinterpret the lyrics—particularly the chorus line, which we swore meant the new boyfriend got “it” all over the ex. Leave it to the ’80s to make a chart-climbing power ballad out of heartbreak, innocence, and a slightly sticky double entendre.

296

Duran Duran

"The Reflex"

1984

Duran Duran were always a clever band, mixing hair bleach, rouge, and pop hooks to become one of the biggest acts of the early ’80s. There was no question they had the goods, but it wasn’t until “The Reflex” that some Black kids started paying attention. That shift came courtesy of Nile Rodgers, whose remix transformed the track with looping background vocals and a funkier, more danceable beat. Some record execs reportedly pushed back, saying the mix was “too Black.” As usual, that turned out to be a compliment in disguise—“The Reflex” became the band’s first U.S. number one and a global smash.

295

Corey Hart

"Sunglasses at Night"

1983

Canada occupies so much space on the earth's surface yet has contributed so little to humanity. I've been to Toronto and thought that it was a very clean and charming city. But like everything else Canadian, it had no edginess to it. While there, I went to a gay event there—OK, it was a bathhouse—and it was just a bunch spice-less Asian boys chasing after a bunch of bland white dudes. Even the men of color I met were like, I don't know, mundane. Cute and mundane. Just like Corey Hart. Still, he needs to be elected president because, besides Joni Mitchell, David Foster, Kaytranada and Canadian bacon, Hart remains the best thing that country has ever exported.

294

Justin Timberlake

"Rock Your Body"

2002

Back in kindergarten, there was this awkward kid named Charles Wyatt with giant magnifying-glass glasses who had a bizarre habit: he’d jump on the backs of the Black kids during recess and start bouncing like he was at a rodeo. Only the Black kids. Even at five years old, we all knew something wasn’t right. Years later, whenever I see Justin Timberlake doing his watered-down MJ moves or trying to channel Prince with that “ain’t-I-sultry” smirk, I get serious Charles Wyatt flashbacks. JT is the musical version of someone who jumps on the backs of Black brilliance and rides it all the way to the top, pretending he invented the saddle.

Thankfully, Pharrell came along and sprinkled some actual flavor on Justin’s career. “Rock Your Body” is a damn good track—smooth, funky, sexy—and the one true highlight of a discography I have never heard and never will. That Neptunes beat does all the heavy lifting, and Justin just gets to glide on top like he’s at an R&B amusement park, all Charles Wyatt-like. Honestly, if Pharrell hadn’t shown up when he did, JT might’ve been the most rhythm-deficient Mouseketeer since Annette Funicello.

We will not see Justin Timberlake again on this countdown.

293

The Cars

"Just What I Needed"

1978

“I don’t mind you coming here / And wasting all my time, time.”

I can’t explain it, but when Benjamin Orr repeats “time”, I kinda lose my mind, mind. It’s just about the best thing in rock music. Period.

The Cars are one of those bands people forget to remember, but between 1978 and 1985 they cranked out a slew of pop-rock gold. Ric Ocasek may not have gotten all the songwriting flowers he deserved while he was alive—or maybe he’s just better remembered as the dude who looked like a praying mantis and somehow pulled Transylvanian supermodel Paulina Porizkova. Either way, “Just What I Needed” is an absolute romp, with that spiky guitar line, stiff-hipped rhythm, and just enough sarcasm to make it cool.

Every time it comes on, I find myself doing that involuntary White Man Stompy Dance. You know the one. Don’t act like you don’t.

292

Talking Heads

"Psycho Killer"

1977

My first exposure to Talking Heads came courtesy of MTV and the hypnotic weirdness of “Once in a Lifetime.” (Same as it ever was!) The guy on screen was all jittery and sweaty, moving around like he was having a full-on conniption fit. And I loved it.

It would be years—decades, really—before I discovered an even better Talking Heads song: 1977’s “Psycho Killer.” Unlike the art-funk of “Lifetime,” this one’s a more straight-ahead rock number, but David Byrne’s eerie vocal delivery and the lyrical content make it even more arresting. Those iconic fa-fa-fas were reportedly inspired by Otis Redding’s “Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa (Sad Song),” but that’s where the comparisons end.

With its stabbing drums and droning bassline, “Psycho Killer” has a twitchy sense of urgency that makes it one of the definitive statements from one of the most legendary bands of the new wave era.

291

Stephen Bishop

"On and On"

1977

Yacht Rock rules, period. And while Stephen Bishop may not have sailed quite as high as Christopher Cross or Captain Kenny Loggins, he definitely steered his own smooth vessel into the heart of the genre. The man had Chaka-freakin’-Khan singing on his 1976 debut album—if that’s not instant cred, I don’t know what is.

“On and On” is one of those perfectly bittersweet, sun-drenched tunes that probably still wafts through elevators, grocery stores, and dentist offices across America—but don’t let that fool you. It’s pure melancholic magic. I remember loving this song as a kid, and somehow, that love never left. It’s breezy, it’s wistful, and it still goes down like a rum punch at sunset.

290

Joss Stone

"Fell In Love with a Boy"

2003

Can someone check on Joss Stone—did she fall asleep at the mic when she recorded “Fell in Love with a Boy”? Because if so, she somehow managed to doze off into greatness. Joss wasn’t playing around on her debut studio album. Not only did she enlist ?uestlove and the legendary Betty Wright to produce the lead single, but Wright also pulled in none other than Angie Stone to lend her velvet-rich vocals to the background. That’s a flex.

The song itself is a sultry reimagining of The White Stripes’ garage-rock stomper “Fell in Love with a Girl.” Where Jack and Meg went for gritty, sped-up punk fury, Joss and her crew slowed it all the way down to a soulful ooze, wrapping it in bluesy guitar licks, buttery clavinet lines, and a juicy 70s vibe you could almost sip on. Joss didn’t just sing over the groove—she tiptoed through it, flirted with it, teased it, and made it completely her own.

At just 16, she was already calling on a lifetime of soul and blues influences—some of whom, like Angie, may have literally been backing her up in the booth. The result? A raw, earnest entry into the neo-soul canon, delivered with the same sort of unvarnished passion that Amy Winehouse would also tap into around the same time on her own debut. Joss found kinship in the scene too, working with Raphael Saadiq, Salaam Remi, and even Dave Stewart of Eurythmics fame.

Whether she was half-asleep or wide awake, Joss Stone made a hell of an entrance—and “Fell in Love with a Boy” is still a stone-cold (pun intended) standout.

289

Beck

"Loser"

1993

Critics’ darling Beck burst onto the scene with the slacker anthem “Loser,” planting his flag firmly in the dirt before it was cool. Way before the opioid chic of white-boy angst became a TikTok trend, Beck was already the unofficial spokesperson for the trailer park-meth lab-Gen X Venn diagram. With his loose, lo-fi sound, he offered a refreshing contrast to the brooding, tightly wound grunge that was ruling the airwaves at the time.

While bands like Alice in Chains and Soundgarden sported with vocalists who could peel paint off the walls—Layne Staley’s haunted wail or Chris Cornell’s Olympian howl—Beck strolled in like, “Eh, I’ll just mumble something and see what happens.” And somehow, it worked. His half-baked, laissez-faire delivery didn’t just feel deliberate—it felt revolutionary.

I eventually warmed up to the grunge wave, but Beck had me from the jump. I sang “Loser” so obsessively during a research trip to Zimbabwe that to this day, my local friends there still associate me with that song. Not sure if that’s a compliment, but it’s certainly a legacy.

288

Kylie Minogue

"Can’t Get You Out of My Head"

2001

No song has ever worn its title more accurately than this Minogue banger, a veritable nursery rhyme for the club crowd. With its hypnotic “la-la-las” and finger-paint-simple lyrics, “Can’t Get You Out of My Head” is practically preschool pop—but that’s exactly what makes it genius. Co-written by Cathy Dennis (yes, the same Cathy who begged us to "Touch [Her] All Night Long"), this monster track is structured like a glitter-drenched descendant of New Order’s “Blue Monday,” built for maximum replay and repeat. Resistance is futile.

It’s the “I Will Always Love You” of dance-pop: Minogue’s signature track and one of the best-selling singles in global pop history. Even if your idea of fun is listening to b-sides from Aphex Twin in a basement, this song is a brain worm that will still creep soul and lay eggs. You don’t have to love it—but once you’ve heard it, you will be humming it during your next grocery run. Catchier than COVID, "Can't Get You Out of My Head" is a perfect storm of mindless deliciousness.

287

Fleetwood Mac

"Say You Love Me"

1975

Simplicity and optimism were Christine McVie’s superpowers. Of the three main architects of Fleetwood Mac’s classic lineup, she was the most consistent, content to chase melody over melodrama. While Stevie Nicks conjured moonlit visions and Lindsay Buckingham shredded through emotional turmoil, McVie kept her eyes—and ears—on the prize: crafting songs with hooks that hit the brain’s pleasure center like a spoonful of sugar. “Say You Love Me” is a perfect example. With Buckingham’s jangly guitar and Stevie’s biscuit-and-gravy background vocals adding just a hint of country twang, the song becomes one of many undeniable highlights from the band’s self-titled 1975 breakthrough. It’s sweet, it’s smart, and it sticks—just like Christine intended.

286

AC/DC

"Black In Black"

1980

I don’t care if you grew up on Scottish bagpipes or alpine yodeling—there’s no way your soul didn’t quake the first time you heard the Godzilla-sized riff that AC/DC unleashed on the world with 1980’s “Back in Black.” That opening guitar lick doesn’t just enter the room—it kicks the door off the hinges. Even hip-hop pioneers like Boogie Down Productions (and others) couldn’t resist sampling its raw power. “Back in Black” isn’t just a song; it’s a seismic event, anchoring one of the best-selling albums of all time and solidifying AC/DC as Australia’s greatest export after the kangaroo. Sure, they’ve had other hits—but don’t ask me to name them. As far as I’m concerned, they could’ve applied for early retirement after this one and still gone down as gods of heavy metal.

285

Taylor Dayne

"Don't Rush Me"

1988

As the proud owner of the biggest mouth in ’80s pop, Taylor Dayne rarely gets mentioned when people rattle off the greatest vocalists in popular music. Maybe it’s because her time at the top was brief—two big albums, a flurry of hits, and then poof. Or maybe it’s because we couldn’t quite take her seriously when she rocked that unblended dark weave over her natural lighter hair in the “Tell It to My Heart” video. But let’s be clear: homegirl could sang. On “Don’t Rush Me,” she dials it down a notch vocally, but still manages to give us sass and story—a woman telling some overeager dude that he needs to pump the brakes. It's not quite boot-knockin' time yet. Taylor admits that she's “made that mistake before” by giving up the skins too soon, so this time she’s taking it “slowly, slowly.” Wise choice, Taylor. I just wish her career hadn’t faded away so quickly, quickly because the rapid decline of the career of someone with such tremendous vocal skills should not have been rushed like that.

284

Radiohead

"There There"

2003

Does “There There,” with its brooding groove and prominent bassline, have a touch of—dare I say it?—soul? Shockingly, yes! I love Radiohead, but let’s be real: few people on Earth are as pasty white as Thom Yorke. (Chris Martin might be his only real competition.) So it was a pleasant curveball to hear the band flirt with an R&B undercurrent on a couple of tracks from "Hail to the Thief". No, Yorke isn’t exactly giving us Teddy Pendergrass vocals, but the rhythm section pulses with unexpected warmth and swing. “There There” doesn’t just shine—it glows.

283

Hamilton, Joe Franks & Reynolds

"Fallin' in Love"

1975

I have no idea who these yacht rockers are—or if they have any other hits—but that’s neither here nor there. “Fallin’ in Love” is a breezy little gem, all billowing strings and grand piano flourishes that somehow make that strawberry margarita you're sipping on taste even sweeter. The song floated all the way to number one in the U.S. in 1975, and some 20 years later, dance outfit La Bouche (of “Be My Lover” and “Sweet Dreams” fame) tried their hand at a cover. I haven’t heard it, and I’m pretty sure it La Sucks. I’ll stick with Hamilton, Frank and Reynolds, thank you very much.

282

John "Cougar" Mellencamp

"Paper In Fire"

1987

I love this song. During John Mellencamp’s heyday, there wasn’t a single he released that I didn’t like—well, except for the anthemic and anemic “R.O.C.K. in the U.S.A.” John always tried to position himself as a Lucky Strikes-smoking, pointy cowboy boots-wearing, Rebel Without a Cause-type figure in pop music. But let’s be real: he was crafting R.O.C.K. that was pretty damn M.O.R.

Case in point: between 1981 and 1989, Mellencamp racked up no fewer than 14 Top 20 singles in the U.S. A true rebel doesn’t try that hard to be liked. For comparison, Bruce Springsteen—a far more convincing rebel—had 12 Top 20 hits in that same span, seven of which came from a single album. Bruce sold his soul to the devil once. Mellencamp had a long-term contract with Beelzebub.

Still, Mellencamp was undeniably, authentically Middle American—and nowhere is that more evident than on the twangy, cornfield-stomping “Paper in Fire.” That ain’t no violin closing out the chorus of what I consider his best track. That’s a FIDDLE, goshdarnit!

281

Stevie Nicks

"Stand Back"

1983

Prince didn’t technically write “Stand Back”—he just dropped by the studio, laid down some uncredited synth magic, and bounced. The track was inspired by his own “Little Red Corvette,” so maybe he saw it as a musical loop closing in real time. Prince also famously sent Stevie Nicks the instrumental for “Purple Rain” and asked her to write lyrics for it, but she turned him down—either because she was overwhelmed by the task or just too blitzed on coke to understand the assignment.

There’s no question that Nicks is a rock legend, but her solo career—while it started with a bang—fizzled into a slow simmer. The drugs had taken a toll on her voice, her output, and her sense of direction. Meanwhile, the music world was shifting away from the mystical rock’n’roll she helped pioneer. “Stand Back” was about as contemporary as she’d ever sound, and one of the last major solo hits she’d land.

But chart stats aside, the real legacy of “Stand Back” lives on in the hearts of gay men everywhere. That video—Nicks gliding on a Planet Fitness treadmill, buried in ten pounds of chiffon, and stomping in skyscraper platform boots—cemented her status as a gay icon for the ages. Sometimes legend isn’t about longevity—it’s about that one unforgettable look that turns out to be unintentionally campy, yet effective.

280

Golden Earring

"Twilight Zone"

1982

Golden Earring were Dutch and had been churning out tunes since the early ’60s. They finally made a real dent with 1973’s “Radar Love”—a song that made no impression on me because it sounds like every other song that sounds like that song, if that makes any sense. It employs the same fast and gritty formula that always ends up playing on the cassette deck in some dude’s Camaro.

But it was “Twilight Zone” that really stood out during the alt-rock invasion of the early ’80s. Dropping alongside gems like “Der Kommissar” (Falco) and “Who Can It Be Now?” (Men At Work), this track rode the wave of international new wave and gave Golden Earring their second U.S. hit. And unlike a lot of bands trying to modernize their sound back then, they actually pulled it off.

Let’s be honest: The Dutch haven’t exactly flooded the world with pop music brilliance. (Eddie Van Halen being their undisputed MVP.) But “Twilight Zone” earns its spot on the short list of great Dutch exports. It’s paranoid, punchy, and a total doozie that rocks!

279

Queen

"Somebody to Love"

1976

When it comes to singers, white people often have no idea what they’re even talking about. The inclusion of Bob Dylan, Lou Reed, and Joan Baez on those so-called “Greatest Singers” lists only proves my point. But every now and then, they get it right. Whoever signed Queen back in the ’70s clearly recognized they had something extraordinary on their hands.

Some of my favorite white male vocalists come from the grunge corner of the map, but when we’re talking pure vocal talent? Buck-toothed Freddie Mercury had no equal. His performance on “Somebody to Love” is Exhibit A—a soulful, towering display of vocal mastery that transforms a pretty standard rock gospel tune into a moment of pure magic. The song itself may not be revolutionary, but what Freddie does with it? Unbelievable.

His voice floats, shimmers, rises, collapses, soars again. That slightly unsteady vibrato manages to radiate both swagger and vulnerability, a combination rarely heard in rock and practically unheard of from a frontman. It’s theatrical without being overwrought, and deeply felt without turning into a sob story. The whole thing is so dynamic and deliciously dramatic, it ranks as one of Queen’s most satisfying singles with a vocal performance that Mercury admitted that he fashioned after Aretha Franklin, a singer he absolutely was fascinated by.

Mercury wasn’t just a great vocalist—he was a performer in the truest sense: bold, fearless, magnetic. And on “Somebody to Love,” he reminded everyone exactly why he was both the King and Queen of rock.

278

Lisa Stansfield

"You Can't Deny It"

1989

The British recording industry has always had a love affair with Black American soul—but when it came to producing their own version of it, they preferred to put it in the hands (and throats) of white women. The list of Black British soul singers who are actually Black women is damn near as short as a Kardashian relationship.

Thankfully, a few of those white ladies showed up and showed out—Lisa Stansfield being one of the best to do it. She had a strong run on both the pop and R&B charts through the late ’80s and ’90s, and one of her standout tracks is the delightfully peppy “You Can’t Deny It.” The song is equal parts Barry White (that plush melody and groove) and Soul II Soul (those unmistakable beats), held together effortlessly by Stansfield’s smoky, impeccable vocals. Love me some Lisa!

A quick note to the British Empire: I appreciate you sending us Lisa from across the pond—truly, I do. But you’re seriously telling me, Britain, that not a single Black woman was available to sing songs like this? Really? Maybe it’s time to rename the whole damn place the Isle of Wight.

And while I got you on the line, can one of ya’ll come get yo’ boy Harry and his “Black” wife? Cheers!

277

Duran Duran

"A View to A Kill"

1985

Let’s keep this one short: Sorry, boys of Duran x 2, but the success of “A View to a Kill” has very little to do with y’all. This track bangs for two reasons—producer Bernard Edwards and (probably) the uncredited drumming of Tony Thompson.

That last part is technically conjecture, but come on. Just listen to the explosive drum work here—it’s unmistakably Thompson. If you’ve heard the best tracks from The Power Station, you already know that signature, bombastic style. It’s all over this song.

Honestly, anyone could’ve sung “A View to a Kill” and it still would’ve been a hit. That said, I’m not mad it ended up with Duran Duran—a pop outfit I genuinely liked back in the day. And it’s no coincidence that their best songs, like this one and the remixed version of “The Reflex,” just happen to involve the boys from Chic—Bernard Edwards and Nile Rodgers. Enough said.

276

The Cure

"Pictures of You"

1989

Look, if you’re trying to shake off depression, don’t waste your time dressing in all black, teasing your hair up to Jesus' house, drawing eyeliner lines under your eyes, and smearing red lipstick across your mouth because it ain’t gonna help. The Cure’s Robert Smith has been doing that for fifty years, and judging by the dreary sound of their 2025 album, it's done nothing to snap him out of it.

Back in 1989, "Disintegration" dropped like a velvet boulder and made bone-deep sadness fashionable for moody teens all over the world who were standing on an emotional ledge. “Pictures of You,” the fourth single from that towering album, wasn’t here to cheer you up—it was here to push you over the edge, slowly and beautifully.

The track opens with a long, swirling intro that feels like sinking into a dark waters. Then Smith’s voice emerges—not to comfort, but to confirm every ache you’ve been trying to ignore. There’s longing. There’s grief. There’s the quiet devastation of memory.

“Hold for the last time / Then slip away quietly”

I don’t have the numbers, but I wouldn’t be surprised if heroin overdoses saw a spike around the time this song hit the airwaves. “Pictures of You” doesn’t just flirt with despair—it gives it a long, passionate kiss. But what a stunning soundtrack for slipping into the abyss. Clocking in at 7 minutes and 30 seconds, not a single second feels wasted. Smith bleeds out every last ounce of emotion, and in doing so, leaves the listener gutted but grateful.

“Pictures of You” was just the beginning of the extended depressive episode that is "Disintegration", an album often called the greatest in rock history—and honestly, I’m not here to argue. It’s more than a collection of songs; it’s a beautiful, brutal therapy session, played in the key of heartbreak. And somehow, it makes you want to feel all of it again.

275

The Alan Parsons Project

"Eye in the Sky"

1982

British outfits like The Alan Parsons Project and Supertramp are the undisputed kings of Spooky Soft Rock—a genre I just made up, but one that absolutely exists. And sitting right at the top of that spectral soundscape is “Eye in the Sky,” a smooth, haunting gem that still rocks in every haunted house across the globe.

As a kid, I remember being genuinely afraid to watch the video for “Don’t Answer Me” alone. Something about that stiff, stop-motion comic book animation, paired with those eerie, flat Alan Parsons vocals, sent a chill through my Black ass. But the “Prime Time” video? Even worse. With its crude mannequins brought to life by the devil and fall in love, made more disturbing by the even cruder and crickety special effects. Why can’t Britons just be normal?

But fear or no fear, I couldn’t stop listening. “Eye in the Sky” is one of their best—floating somewhere between lullaby and alien transmission. And if you’re going to listen to it (and you should), make sure you hear the full album version that starts with the instrumental intro “Sirius.” That cosmic opener, by the way, is the same music the Chicago Bulls use at home games to announce themselves before getting their asses whipped by whatever team’s visiting that night.

274

REM

"Man on the Moon"

1992

There’s just something inherently whiny about Michael Stipe—and Michael Stipe’s singing, isn’t there? Back in college, I made several attempts to hop on the R.E.M. bandwagon, but I kept falling the fuck off. Every time I tried to get into them with tracks like “Orange Crush,” “The One I Love,” or “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine),” they’d pull me right back out with diarrhea-inducing fluff like “Shiny Happy People” or the nonsense of “Stand”, a song not fit for Sesame Street muppets.

But as I got older—and maybe just a little more forgiving—I did the right thing and dove into their early catalog. I started streaming songs from back when R.E.M. ruled college radio, up until around 1987, and things began to make more sense. Now I could hear why they were such critic darlings. These weren’t just the guys who gave us just-OK hits like “Losing My Religion” and “Everybody Hurts.” There was real artiness there. Mood. Texture. Purpose.

Even after breaking through commercially, they still released some solid singles—like “Man on the Moon,” their open letter to Andy Kaufman. It’s a little bit country, a little bit rock and roll: the verses float along, echoey and reflective, and then the bridge and chorus come in with real melodic heft. It’s catchy in a way that doesn’t feel pandering, which is not something I could say about their early ’90s output across the board.

It was refreshing to hear Stipe loosen up for once—especially after the joyless dirge that was “Losing My Religion,” which attacked our ears like a nagging, unhappy spouse for all of 1991. These days, I’ve come to appreciate R.E.M. more—particularly when Stipe avoids his worst Dylan impressions and lets a little clarity, wit, or even warmth slip through the fog.

273

Michael Sembello

"Maniac"

1983

You can try, but you’ll only drive yourself crazy if you attempt to separate this song from the choppity-chop, high-knee dancing made famous by Jennifer Beals--oops, I meant Jennifer Beals’ double--back in the ’80s. “Maniac” is permanently fused to that iconic scene in "Flashdance", and there’s just no pulling them apart.

Back then, it was impossible not to see hit movies. That’s what people did before the internet. You either caught films like "Flashdance" in theaters, or you waited for HBO to finally bless your household with a screening. Movies like "Top Gun", "E.T.", and "Back to the Future" weren’t just popular—they were cultural oxygen. And "Flashdance" belongs on that same tier, even if I’m probably the last Gen Xer alive who still hasn’t actually seen it.

Still, I know iconography when I see it. The off-the-shoulder sweatshirt? The leg warmers? Those were everywhere—on school campuses, in JC Penney catalogs, even showing up on Halloween costumes for years afterward. And the dancing in the video for “Maniac” is so culturally embedded, it feels as familiar to me as my own reflection.

Michael Sembello—a name I had already recognized from Stevie Wonder liner notes—found himself smack in the middle of a very specific cultural moment. No matter how accomplished he is as a musician (and he is), he’ll forever be linked to the glorious cheesefest that is "Flashdance". But honestly? That’s not a bad thing. It’s better to hit the charts once than not at all—because folks with no hits don’t get written about in columns like this one.

272

The Family

"The Screams of Passion"

1985

I guess it’s too late to ask Prince why he had The Family dancing around in pajamas. The Family were one in a long line of musical, um, groups he created to exert control over a love interest. The project centered around Susannah Melvoin, twin sister of Revolution guitarist Wendy Melvoin and the woman Prince happened to be madly in love with at the time. She was his muse during one of his most emotionally fertile periods, inspiring songs like “If I Was Your Girlfriend” and The Family’s own “Nothing Compares 2 U.”

Susannah herself will be the first to admit she wasn’t much of a musician, but that didn’t stop Prince from building an entire band around her. And oddly enough, The Family’s first and only album turned out to be a pretty damn good piece of work—led by the woozy, erotic duet “Screams of Passion,” sung by Susannah and St. Paul Peterson.

The track is unmistakably a Prince song—it just happens to be sung by someone else. I remember watching an interview with Peterson, in which he admitted how frustrated and stressed he was during the recording sessions. Prince had laid down full vocal demos and insisted Peterson copy them exactly—no room for interpretation, no room for flair. Just mimicry. But even that didn’t really matter, because the album vanished into thin air upon arrival. Prince and Susannah had broken up before the record even dropped, and as with many things in the Purple One’s orbit, once the romance ended, so did his interest in promoting anything related to said romance.

Sure, Sinead O’Connor later brought the world to its knees with her version of “Nothing Compares 2 U,” and that probably sent a few curious listeners hunting for The Family’s original version—but good luck finding it at your local wrecka stow. (Thankfully, I’ve got my copy of the original LP tucked away in a closet somewhere, safe and sound.)

271

Eurythmics

"Love Is A Stranger"

1983

The Eurythmics have a storied career, but “Love Is a Stranger” stands out as one of their most satisfying achievements—not just for Annie Lennox’s eerily emotive vocal delivery, but also for Dave Stewart’s subtle, razor-sharp production choices. The Brits don’t get much sunlight, so maybe it’s no surprise that so many of their best songs sound like they’re in desperate need of a Prozac prescription—and “Love Is a Stranger” is no exception.

Released as the first single from their breakthrough sophomore album "Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)", the song feels like an invitation into the haunted house you can't help accepting. It doesn’t just play—it slithers out of the speakers and drapes itself across the room like spiderwebs. The synths shimmer like moonlight through broken glass, while Lennox’s voice—blessed by none other than the Good Lard himself—glides and harmonizes with itself in ethereal layers. She doesn’t just sing the song; she possesses it, or maybe it possesses her.

Though “Love Is a Stranger” flopped upon its initial U.S. release, its reissue—riding the tidal wave of “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)” topping the charts—pushed it to a respectable No. 23 on the pop charts. And from there, the duo embarked on a remarkable run of hits throughout the ’80s, culminating in a legacy that carried them all the way through to their final disbandment in 1999.

Creepy, glamorous, and perfectly executed, “Love Is a Stranger” is art pop with a slow pulse—and a slightly menacing grin.

270

Teena Marie

"I Need Your Lovin'"

1980

Teena Marie somehow never shows up on those ridiculous Rolling Stone “Greatest Singers” lists, like she’s the victim of some weird, backwards racism on the part of white critics. Her voice was too Black to be placed on the same pedestal as Patti Smith, but because she was white—through no fault of her own—they wouldn’t dare mention her in the same breath as Whitney or Etta either. She existed in a kind of critical limbo, punished for sounding too soulful and not looking the part.

Only Amy Winehouse managed to walk that tightrope—embraced by white critics and still respected across genres. But let’s be clear: that wasn’t because she was a better vocalist or more deserving than Teena. It was because they chose to prop her up. Critics needed an edgy, retro, soul-slinging white girl they could romanticize. And Amy fit the bill. Teena, on the other hand, had too much authentic funk and fire to ever be a safe media darling.

Now, I’ll admit—I was never a deep Teena Marie head. I didn’t own her albums, and beyond “Square Biz” and the undeniable “Fire and Desire” duet with Rick James, the song I remember most from her growing up was “I Need Your Lovin’.” That track rides the line between disco and funk with precision, and Teena works it from start to finish. Her voice is muscular, emotive, and endlessly flexible—far more than just competent. It’s a showcase.

So yeah, fuck Rolling Stone and their lazy, predictable lists. I’m going on record right here and now: Teena Marie was the best white female singer in the game. In front of Dusty, Joss, Amy, and Lisa Stansfield. Full stop.

269

Soundgarden

"Black Hole Sun"

1994

If we’re naming the best singers by genre, I’d have to put Chris Cornell—of Soundgarden and Audioslave—at the top of the grunge list. And when it comes to rock vocalists overall, he’s easily top two or three. No question.

When grunge first exploded in the early ’90s, I didn’t pay much attention. I wasn’t blown away by Kurt Cobain (no pun intended), and to me, grunge just felt like more of the same noisy guitar rock that had already been clogging up radio playlists. But with time—and a more open mind that only aging can bring—I started to hear something deeper in some of those bands, especially Soundgarden and Alice in Chains. That’s when it hit me: this wasn’t just flannel and feedback. There was craft in the chaos.

“Black Hole Sun” marked Soundgarden’s big commercial breakthrough, and the video alone was enough to make Stephen King take a few uncomfortable steps backwards. Grotesque, surreal, and unforgettable. But what really makes the track last isn’t the disturbing visuals—it’s the voice. Cornell’s performance here is remarkably restrained, perfectly mirroring the song’s eerie, melancholic tone. He’s not screaming his lungs out (though he certainly could have); instead, he’s hovering—haunting, almost spiritual. It proves that he wasn’t just a wailer; he was a true interpreter of mood and melody.

I still have no idea what “Black Hole Sun” is actually about—and honestly, I don’t need to. That’s not the point. The point is Cornell’s voice, a thing of wonder that could wrap itself around a whisper or a howl with the same intensity. And we’ll be hearing more about him in this column—guaranteed.

268

Elton John

"Sad Songs (Say So Much)"

1983

If I ever found myself at some emotional crossroads, ‘80s-era Elton John would probably be the last person I’d turn to for wisdom or comfort. His music from that period doesn’t exactly wrap me in a warm blanket of solace. But credit where credit’s due: when he tells us to “turn ’em on!”—referring to those sad songs—that’s actually some solid life advice right dere.

“Sad Songs (Say So Much)” bops along atop some bright, bouncy piano shit that makes me question whether this is even a sad song at all. I mean, the white folks dancing under an open fire hydrant and doing somersaults in the video don’t seem particularly heartbroken. Neither does Elton, prancing around in a straw party hat looking like he’s on his way to a retirement luau.

But that’s the beauty of the track: it’s not actually about sadness, just like Johnnie Taylor’s “Disco Lady” is not a disco song. It’s about the function of sadness. It’s a celebration of how music, especially the sorrowful kind, can express what we often can’t. Sad songs are the quiet companions that show up when we feel like no one else gives a damn about our sorry ass, when we’ve wrung out the last drop of faith. They sit next to us in the dark, patting us gently on the back whispering "there, there."

This is an oddly uplifting ditty that reminds us there’s something cathartic, even life-affirming, about hearing a song that mirrors our lowest moments.

And shout out to Sassoon, by the way, for that glorious 1980s-era commercial where they flipped the lyrics to say “Sassoon says so much.” Ooh la la la, indeed.

Don’t worry—Elton will show up later in this countdown with a truly sad song. But for now, we’ll let this one remind us that sometimes, dancing to despair is the best therapy we’ve got.

267

Genesis

"No Reply At All"

1981

Is Phil Collins a singer who drums or a drummer who sings? According to Collins himself, he’s firmly in the latter camp—and “No Reply at All” makes a strong case for that. On this track, the drums are so prominent in the mix, they’re practically duetting with his lead vocal. And honestly, that’s a good, good thang.

“No Reply at All” was one of the standout singles from "Abacab", Genesis’s eleventh album, released in September 1981. By this point, the band had fully pivoted away from the abstract oddities of their prog-rock years—an era nobody really understood outside of a few Brits and maybe some University of Vermont teens who smoked a lot of weed—and leaned into something far more accessible. That pivot actually began the year prior with 1980’s "Duke" and continued with Collins’ own solo debut "Face Value", which had dropped in January of that same year.

But "Abacab" solidified the transition, and “No Reply at All” was a prime example of this new Genesis: punchy, tight, and radio-ready. A huge part of that punch came courtesy of the Earth, Wind & Fire horns, arranged by the legendary Tom Tom 84 (Thomas Washington). Those horns gave the song a brassy, stutter-stepping edge, accentuated by faux handclaps and an almost funk-adjacent rhythm section that was a world away from twelve-minute suites about goblins and mythical kingdoms.

The song’s emotional core comes from the same bitter well that fueled much of Collins’ work at the time. He was dealing with the painful dissolution of his marriage, and that rawness seeps into “No Reply at All” just as it does in “In the Air Tonight” and “Misunderstanding.” Even when the arrangement is upbeat and almost danceable, there’s a biting, lonely ache in his voice—an emotional contradiction that Collins did well back in those days.

In the end, “No Reply at All” charted respectably in the U.S. Top 30 and did even better in the UK and Canada. It’s not just a catchy single—it’s a watershed moment in the Genesis/Collins timeline, marking the point where progressive rock gave way to emotional accessibility without completely losing its complexity.

So yeah, he’s a drummer who sings. And when both of those skills are firing on all cylinders, as they are here, everybody wins.

266

The Jets

"Make It Real"

1987

Normally, I’d say something like this as hyperbole: There were 17 of them Jets! But this time, I’m telling the damned truth. The Chinese army had fewer members than this brood of Minnesotan kids of Tongan descent. Known to the world as The Jets (last name: Wolfgramm), they stormed the mid-’80s charts with six Top 20 hits on both the R&B and Pop charts between 1985 and 1988.

Their debut was powered by the songwriting and production talents of Jerry Knight—yes, the stronger voice from Raydio and one half of Ollie & Jerry (see: “Breakin’…There’s No Stoppin’ Us”). That first Jets album gave us no fewer than four hit singles. Their follow-up, "Magic", delivered another four, including their final charting hit: “Make It Real.”

Even though lead vocalist Elizabeth Wolfgramm was only 13 or 14 when she recorded the track, it’s clear the group were seasoned pros by that point. They’d been performing live for years before the industry even came calling. With its stripped-back production, tinkling keyboard line, and slow-dance tempo, “Make It Real” was tailor-made for that moment at the prom when the DJ leans into the mic and says, “Alright, let’s slow it down a bit…”

Elizabeth delivers the song exactly as written—no runs, no ad-libs, no oversinging. And that works. The simplicity of her approach makes the emotion land even harder. There’s a soft sadness in her voice, a kind of adolescent ache that helped turn “Make It Real” into one of the most quietly devastating breakup ballads of the late ’80s.

The Jets may have rolled deep, but in this moment, it was just one voice, one heartbreak, and one timeless slow jam.

265

The Clash

"Rock the Casbah"

1982

I was in elementary school when “Rock the Casbah” came out, and I had never heard of The Clash and didn’t know what that fuck a casbah was. (Still don’t.) From the look of the video, it seemed vaguely Middle Eastern-ish, but none of that mattered. A great song with a great hook is a great song with a great hook, and this one hit hard.

With its aggressive, almost funk-defied drumbeat, bluesy piano flourishes, and slicing rhythm guitar, “Rock the Casbah” marked a stylistic shift for The Clash. The band, already legends in the waning punk scene and beloved by indie radio purists, were stepping into something bigger, bolder, and way more danceable. When their fifth album "Combat Rock" dropped, The Clash officially broke into the U.S. market—and MTV helped make them stars.

Of course, nothing gold can stay. By the end of the "Combat Rock" cycle, the band was already falling apart. Drummer Topper Headon, who wrote the music for “Rock the Casbah,” was fired for drug issues. Guitarist Mick Jones didn’t last much longer. That left Joe Strummer and bassist Paul Simonon to limp into one final album before The Clash officially imploded.

Joe Strummer passed away in 2002—just one year before the band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. It was a bittersweet ending for one of punk’s most important bands, but at least they left us with an unexpected banger like “Rock the Casbah”—a song that, even without knowing what the hell it means, still hits like a revolution in a leather jacket.

264

Steve Perry

"Foolish Heart"

1984

Look a-here. I know the people who lived and died by Iron Maiden and Metallica hate the Milton Bradley-brand rock bands like Journey, REO Speedwagon, and Styx. Too soft, too clean, too… wimpy. Black folks did the same thing when we gave the collective gas face to lightweight rap acts like MC Hammer and P.M. Dawn. Didn’t stop them from climbing the charts, though.

Same goes for Journey. Hard rock purists can scoff all they want, but Journey’s Greatest Hits album has gone 18x platinum—that’s one copy for every single person currently living in Senegal with a few hundred thousand left over. Hate all you want, but somebody’s buying this crap.

And let’s not pretend the secret to Journey’s success was a mystery: it was Steve Perry. That voice. That once-in-a-generation wail that could glide like silk one minute and rasp like sandpaper the next. In 1984, Perry took a break from Journey and dropped his first solo album, "Street Talk". A couple of singles came out of it, but the one I care about—the one that still lingers—is “Foolish Heart.”

“Foolish Heart” is a mid-tempo ballad dipped in just the right amount of sadness, the kind of soft ache that hits late at night when you’re trying to lie to yourself about that lover who don’t love you back. There are no bells or whistles here—just Perry’s raw, husky vocals sitting front and center, where they belong, cradled by soft ’80s synths and gentle drum machine programming. His voice had aged a bit by then, roughened around the edges, but that only made the heartbreak sound more believable.

Perry would go on to record two more albums with Journey before parting ways for good. He continued to release solo work, but slowly drifted into near-reclusion—especially after the death of his girlfriend in 2012.

So yeah, maybe Journey wasn’t hard enough for the denim-jacket crowd. But for the rest of us? Sometimes, all it takes is a foolish heart—and Steve Perry singing straight to it.

263

Madonna

"Dress You Up"

1984

The main reason I don’t dog young people for their music is simple: I can’t possibly grasp how deeply today’s artists resonate in their lives. Kendrick Lamar, Beyoncé, and Ariana Grande are all great at what they do—but they don’t and can’t define any meaningful chapter of my life. I was already fully formed by the time they hit the scene. Just like I wouldn’t expect an 18-year-old today to truly understand what Madonna meant to us when we were coming of age.

To say Madonna was “big” is a gross understatement. She wasn’t just a pop star—she was a cultural detonator. Her influence extended far beyond music: into fashion, personal identity, gender politics, MTV aesthetics, and everything in between. By the time “Dress You Up” dropped, her blockbuster "Like a Virgin" album had already been out for eight months and birthed two mega-hits. Add the soundtrack smashes “Crazy for You” and “Into the Groove” into the mix, and “Dress You Up” ends up feeling like the afterthought of the album cycle.

But quality-wise? “Dress You Up” is easily the strongest track on the otherwise spotty "Like a Virgin" record, and her best single since “Borderline.” It’s got groove, bounce, sass—and Madonna rides that Nile Rodgers-produced beat hard like it’s some good Jamaican dick.

Even though the label didn’t bother to film a proper video for it, the live concert clip they used instead served another purpose: it gave small-market fans like me (Madonna never toured through Phoenix when I lived there) a glimpse of her electric, confident stage presence. Even from a grainy VHS recording, you could see she was a star with a capital S.

“Dress You Up,” along with “Into the Groove,” also helped reconnect Madonna with her Black audience, charting at #63 on the R&B charts (“Groove” climbed all the way to #19). In the early ’80s, there was simply no escaping Madonna—and truthfully, most of us didn’t want to. Say what you want about her screwy-looking face nowadays, but the legacy speaks for itself: Madonna gave us some of the most unforgettable, genre-defining pop music of our lifetimes. She didn’t just soundtrack an era—she shaped it.

And if you weren’t there? You’ll just have to take our word for it, young-uns. Just like I'll have to take your word for how great Taylor Swift supposedly be.

262

Level 42

"Lessons In Love"

1986

Can Level 42 be classified as blue-eyed soul? Probably not—if you’re only judging by the vocals. Mark King doesn’t exactly croon like Hall & Oates. But listen to that bass. King’s slap-happy playing is straight out of the Larry Graham/Bootsy Collins school of funk. If blue-eyed soul isn’t the right label, then maybe we need to invent a new one for Level 42: white-boy Brit-funk with jazz leanings and serious groove credentials.

“Lessons in Love,” released in 1986, is pure melodic Brit-pop with just enough rhythmic muscle to cross over. And cross over it did, reaching #12 on the U.S. charts—not quite matching the heights of 1985’s “Something About You” (their biggest American hit), but still a solid entry in the mid-’80s UK-to-US pipeline.

Level 42 never quite became a household name, but they consistently delivered jazzy, polished pop that went down easy. “Lessons in Love” is a perfect example of their sound: intricate musicianship cloaked in smooth production. And one of the track’s secret weapons? Keyboardist Mike Lindup’s falsetto bridge—light, angelic, and so soft-focus it could’ve landed him an honorary spot in DeBarge. (Not surprising when you learn that half-caste Lindup is of Belizean descent—his mother was none other than Nadia Cattouse, the acclaimed actress and folk singer.)

No, Level 42 wasn’t chasing soul clout. But they brought enough funk to the table—and enough finesse to the charts—to make a lasting impression. “Lessons in Love” may not qualify as blue-eyed soul, but it’s a textbook case of how British pop in the ’80s could learn a whole lot from Black American music… and still make it their own.

261

Karla Bonoff

"Personally"

1982

I never get tired of saying this: Black folks of my generation love us some Yacht Rock. Sure, the genre was dominated by white men with feathered hair and pastel slacks, but every now and then, a white chick like Linda Ronstadt or Melissa Manchester would float in with a jam worth clinking a champagne glass to. Karla Bonoff’s “Personally” is one of those jams.

Now, I didn’t even know this song existed until well into the 2010s. And I definitely didn’t know that Jackie Moore—yes, the disco queen of “This Time Baby”—had already recorded a version years earlier. (See how Black pop and Yacht Rock keep bumping into each other on the same shoreline?) Vocally, Karla ain’t on Jackie’s level—not even close—and there’s not much difference between the arrangements. But there’s something endearing, even charming, about Bonoff’s version, that lacks of that sexual energy. Maybe it’s the soft, slightly hesitant delivery, like she’s not taking her body to her man personally but just dropping off a casserole.

Bonoff is one of those mostly overlooked, low-profile white women that more famous stars like Wynonna, Bonnie Raitt, and—especially—Linda Ronstadt were quietly stealing from. “Personally” wasn’t even supposed to be her song. Her buddy Glenn Frey had set it aside for Raitt, but Karla politely asked if she could use it for an album he was supposed to produce for her (spoiler: he didn’t). And that wasn’t even her only song jacked by her more glamorous peers—Linda and Aaron Neville lifted their Grammy-winning duet “All My Life” straight from Bonoff’s catalog.

I don’t know if Karla has any other hits, and I’m too lazy to find out. But I do know this: I’m glad she covered “Personally.” It’s one of those smooth, under-the-radar slow sails that’s now required listening any time I take my imaginary yacht out for a spin. No waves, no worries—just a lady with a soft voice and a mysterious package to delivery.

260

Robbie Dupree

"Steal Away"

1980

I know I just said this, but it bears repeating: Black folks my age love us some Yacht Rock. There are no ifs, ands, or buts about it. Toto, Kenny Loggins, Michael McDonald, and Christopher Cross may be the Mount Rushmore of ’70s and ’80s soft rock, but a few lesser-known names also served up hits solid enough to pack in your overnight bag before setting sail.

Take “Steal Away” by Robbie Dupree. On paper, it’s a simple, sweet ditty. But listen closer, and you’ll realize it’s actually about a horny dude trying to secure some stank from a woman he met, like, five minutes ago. Despite the questionable content, the track glides along with charm and sincerity, like all good Yacht Rock should.

And let’s be real: if you like the Doobie Brothers’ “What a Fool Believes”—and I know you do—then you’ll like “Steal Away.” The DNA is unmistakable. So unmistakable, in fact, that the publishers of “Fool” allegedly came after Dupree for biting that keyboard riff. But here’s the twist: Michael McDonald had already jacked that riff from Fleetwood Mac’s “You Make Lovin’ Fun,” so he kept his name out of the lawsuit. (And it really sounds like Michael is ghost-singing backup on “Steal Away” anyway, doesn’t it?)

Robbie Dupree, a Brooklynite, was nominated alongside Christopher Cross for Best New Artist at the 1981 Grammys. We all know how that went—Cross swept in and then vanished almost as quickly as Dupree did. But us Black folks? We still got love for both of ‘em. Need proof? “Steal Away” even squeaked onto the R&B charts, peaking at #85. That means a few Black radio stations made space in their rotation for Robbie, and that’s no small thing.

Good for Robbie. Good for us. And good for Yacht Rock, the genre that quietly united all of our Aunties and Uncles—champagne flutes in hand—under one smooth, synthy groove.

259

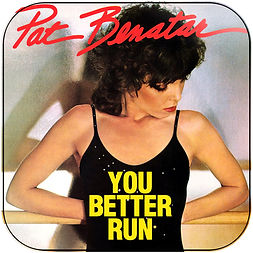

Pat Benatar

"You Better Run"

1980

OK, so I’ve scoured the data, listened to the receipts, and come to the only conclusion that makes any sense: Pat Benatar was the best singer in rock music—male or female.

Now, if we’re talking about men, I’d hand that crown to Freddie Mercury, followed verr, verr closely by Chris Cornell, Layne Staley, and Ronnie James Dio. On the women’s side, other elite rock vocalists include Ann Wilson of Heart, Linda Ronstadt, and the incomparable Tina Turner. (And while we’re here—why do white critics insist on ranking Patti Smith’s scraggily, craggly yowling so high? Stop it.)

Benatar may not have always had the best material, but she had that rare combination of smoothness, bite, clarity, and vocal power that could elevate just about anything she touched. (Think of her as the Whitney Houston of rock: someone who never had to shout to prove she could out-sing anyone in the room.) Pat had the kind of voice that could have flexed across genres—and eventually did, as her rock career dried up like a raisin in the sun.

“You Better Run” is my favorite of her early singles because she absolutely dares anyone to match her level of attitude. She spits the verses with venom, growls and roars through the hook, yet her tone always hits you like a bell. Crystal clear, full-bodied, and bursting with intent. She would later add more emotional vulnerability to her toolkit and take a more mainstream route—but in those early days, it was tracks like this that cemented her legacy as the baddest singing bitch rock music ever had the privilege of claiming.

258

Violent Femmes

"Blister in the Sun"

1983

A surprisingly influential band, Violent Femmes dropped a debut album full of soupy, whiny, acoustic punk that struck a deep, hormonal chord with every seventh-grade white kid with a cassette copy in their My Little Pony backpack.

At my Arizona junior high, these very white dudes from Wisconsin were the truth—at least to the frosted-tip masses who thought they were being rebellious belting out lyrics about being “so strung out” and “high as a kite.” (Honestly, most of them were. This is suburbia we’re talkin’ ‘bout.) But lyrical content aside, “Blister in the Sun” was a catchy fuck of a song, built around a plucky, simple guitar riff that was impossible not to hum as you trudged between Home Ec and gym class.

Lead singer Gordon Gano sang with that specific brand of nasal angst that perfectly mirrored what white suburban teens were feeling in the mid-’80s: pissed, confused, and dying to be just like everyone else. I wasn’t white, and the lyrical themes didn’t really speak to me when they first came out—but I was high as a kite through most of high school, so yeah… I hummed this shit right along with the rest of ’em.

257

Eurythmics

"Here Comes the Rain Again"

1983

The orchestral swells that brush up against the electronic percussive ticks in the opening moments of this song are iconic—chilly, clinical, yet somehow deeply intimate. At the time, there was virtually nothing on the radio that sounded quite like this: synths that felt like snowflakes falling on steel, anchored by one of the most dynamic voices the U.K. has ever shipped across the Atlantic—carrot-topped powerhouse Annie Lennox.

Personally, I have a soft spot for songs written in minor chords. They tend to sound moodier, more introspective, often soaked in a kind of stylish melancholy—and for that to really land, you need a vocalist who can swim in those waters without sinking. Lennox does it effortlessly. Her delivery is restrained but emotionally precise, shadowed and breathy in the verses, rising to a soulful simmer as the song lifts in the final stretch with some beautifully timed ad-libs.

This is a fantastic song that, with just the right push on Black radio, might’ve even slipped into the R&B Top Ten. The mood, the groove, and that voice? All the ingredients were there.

“Here Comes the Rain Again” is just another immaculate piece of evidence that proves that the Eurythmics were 80s royalty.

256

Teena Marie

"Square Biz"

1981

What made Teena Marie so unique is that she didn’t try to sing Black—she just was. Everything about her delivery—the slightly unstable vibrato, the unforced melisma, the occasional church-born growl—came from deep within someone who had soul music coursing through her bloodstream, not just her playlists.

“Square Biz” was my personal introduction to Lady T. It was a massive hit even in Cow Patty County, Arizona, which meant you couldn’t go anywhere without hearing that bass line snapping like plastic barrettes at the end of your ponytails. Co-written by bassist Allen McGrier, the track wisely puts his pop-and-thump front and center—but Teena had the vocal chops (and then some) to ride that groove like a pro. She didn’t just survive the funk—she bent it to her will.

A lot of folks point to the rap verse as the song’s biggest flex—and yes, Teena drops some bars with surprising confidence. But Debbie Harry had already gone there earlier that same year on “Rapture.” No, what truly set “Square Biz” (and Teena Marie in general) apart was the fact that she produced her own damn music. That detail often gets lost in the awe of everything else she brought to the table, but it’s a huge part of why her work felt so intentional, so unmistakably hers.

255

Traveling Wilburys

"End of the Line"

1988

Though there are one or two country artists I really dig, country music itself doesn’t exactly give me a boner. (A hot cowboy in tight Wranglers does, though.)

But country-adjacent rock? That’s when my ears perk up like when a dog hears the can opener. Linda Ronstadt serves this kind of rock. So does Stevie Nicks. Bonnie Raitt? Oh, she practically marinates in it. Even Eric Clapton dabbles now and then. I’m not entirely sure what the official term is—Cracker Rock? Rockabilly? Whatever it is, it walks that line between twang and groove, and I’m here for it.

“The End of the Line” by the Traveling Wilburys fits squarely into that delicious in-between. Jeff Lynne (of ELO fame) is a fine producer, and this track is a great example of his light-touch, sun-drenched approach. But what really jumps out—knocks you sideways, even—is when Roy Orbison’s voice enters. It’s angelic. It’s otherworldly. It’s like the other guys (George Harrison, Tom Petty, Jeff Lynne) are singing around a campfire with marshmallows while Orbison is being beamed down from some velvet-curtained cathedral in heaven.

Thank God Jeff Lynne had the good sense to leave Bob Dylan off this one because his frog-throated croak would’ve just fucked it all up.

Back when this came out, I didn’t know much about Roy Orbison, but the contrast was impossible to miss. His voice demanded attention, elevating what could’ve been a laid-back porch jam into something close to celestial. It’s easy to forget the power of a voice until someone like Orbison steps in and reminds you.

Watching the video for this song made me realize (or remember, rather) that Orbison was already dead before this single was released in January of 1989. He’d died of a heart attack in December at the age of 52, right as his career was experiencing a major resurgence.

It almost gives the song’s title an ironic feel…

254

Erasure

"A Little Respect"

1988

1980s electro-pop has Vince Clarke’s name spray-painted all over it. As the founding member of Depeche Mode, Yaz(oo), and Erasure—in that order—Clarke was the sonic architect behind some of the era’s most enduring synth-driven anthems. In the U.K., Erasure were just as big as Depeche Mode, and the pairing of Clarke’s bright, bouncy production with Andy Bell’s flamboyant and soulful vocals gave us more than a few pop masterpieces—chief among them: “A Little Respect.”

Andy Bell is no Aretha, but he sings with a touch of gay soul that feels like your Black Aunt Kay-Kay got herself a drum machine and a glitter mic. His voice, while not as smoky as Yaz’s Alison Moyet, shares a similar emotional pull—tender, urgent, and just the right amount of theatrical. And while “A Little Respect” is built on the electronic bones Clarke is famous for, the acoustic guitar strumming through the track adds a charming, human heartbeat that gives it crossover appeal.

The song is pure pop gold—uplifting, dramatic, and sing-along ready—and it’s just one of many gems in Erasure’s catalog. I don’t own any full albums by them, but "Pop! The First 20 Hits" is a must-have for anyone looking to inject a little 80s-era sparkle into their day.

253

OMD (Orchestral Manœuvres in the Dark)

"If You Leave"

1986

Researching this blog revealed that OMD (Orchestral Manœuvres in the Dark) were actually a pretty influential force in the late-’70s electronic music scene. I may have to take a minute and check out their early catalog. Then again, I probably won’t.

The truth is, I’m perfectly content with “If You Leave” being the one—and possibly only—OMD song I carry with me through life. OK, let me stop lyin’: I also know “Secret” and “(Forever) Live and Die,” and they’re just fine. But “If You Leave” towers over them like when Shaq and Kevin Hart show up for the same event.

If you were in junior high or high school in the 1980s—and this part is crucial—and you grew up in the suburbs and/or surrounded by white people, movies by John Hughes and songs like “If You Leave” helped define your teen years. Full stop. “If You Leave” is from a movie I’ve never even seen ("Pretty in Pink"), but I cannot hear this song without picturing Molly Ringwald’s scraggly little face full of freckles looking both angsty and oddly hopeful.

This song instantly teleports me back to school dances in the gym and marathon weekends watching MTV when it actually played music videos. It’s a gorgeous slice of synth-pop melancholy that would’ve worked just as well coming from ELO, ABC, or the men’s choir at BYU.

I hold “If You Leave” close, not just because of how it sounds, but because of what it evokes: a perfect little time capsule from a weird, wonderful, coming-of-age era that, for many of us, will never quite be topped.

252

Alice in Chains

"Rooster"

1992

My brain is pretty good at producing most emotions on its own—happiness, anger, bitchiness—but I’ve never been able to create sadness or depression, so to keep myself balanced, I have to get those feelings from somewerrr else. That’s where my love of sad songs comes in, and those mournful harmonies that open “Rooster” provide all the gloom I need for the day.

Layne Staley was a magnificent vocalist, and something tells me he didn’t have an easy time producing joy either, which made him the perfect interpreter of the doom-heavy rock Alice in Chains specialized in. “Rooster” tells the story of a Vietnam vet—guitarist Jerry Cantrell’s father—and Staley delivers it like he’s the one stomping through the jungles. His emotion here is raw and gripping, capturing the horror and futility of yet another war that made no damn sense.

(And just in case you were wondering, as I’m sure you were—my favorite rock song about the perils of war is Metallica’s “Disposable Heroes.”)

I also appreciate that the video includes the suffering of soldiers on both sides. You know who else are Vietnam vets? The Vietnamese.

And by the way, even if “Rooster” sucked, it would still be worth it just for the way Layne sings, “The path leads me to nowerrr / The bullets scream to me from somewerrr.” That’s gold.

251

Pet Shop Boys with Dusty Springfield

"What Have I Done to Deserve This?"

1987

From Erasure to Dead or Alive to the Pet Shop Boys, the 1980s did little more than confirm that all the gayness in the world originated in the U.K.

Neil Tennant could sing, but he wasn’t really a singer. He could sort of rap, but he wasn’t a rapper either. What he brought to the mic was a uniquely aloof, swishy charm that worked beautifully for the Pet Shop Boys’ brand of icy, brainy electro-pop—but maybe that’s part of why they never became the massive American pop force they deserved to be.

On paper, adding a blue-eyed soul legend, the legendary and lesbianic Dusty Springfield, to the mix should’ve made things worse for the fortunes of the Pet Shop boys. But it didn’t. In fact, “What Have I Done to Deserve This?” needed a real voice to anchor it, especially during the bridge (“Since you’ve been away…”) where Dusty’s warmth takes the song from clever to classic.

Several big-name singers were considered for the duet, but none of them felt right. Even when Springfield was first approached, she turned it down—she didn’t know who the Pet Shop Boys were. But after learning more about their success (and probably eyeing some bills stacking up on the kitchen counter), she agreed, and two years later finally flew from L.A. to London to record her part. What resulted was a fabulous song that hits on all cylinders: it’s danceable, melodic, and catchy as it wanna be. And it’s the tenderness of Springfields smooth vocals that contrast with Tennant’s even-keeled delivery that gives the song its glow.

The single became Dusty’s first real hit in nearly two decades and gave her a graceful return to the charts as well as some much-needed grocery money. It also handed the Pet Shop Boys their biggest U.S. hit since “West End Girls,” helping make “Actually” their best-selling album.

At her funeral in 1999, Elton John called Springfield “the greatest white singer there ever has been”—making a point to add the “white” part, presumably because he didn’t want the famously testy Aretha Franklin to burn one of his mansions to the ground.

250

Wang Chung

"Dance Hall Days"

1983

Where was the #MeToo movement when we needed it?

Am I the only one getting serious sexual assault vibes from “Dance Hall Days”?

Let’s take a closer look:

“Take your baby by the heel / And do the next thing that you feel.”

Absolutely not. You can’t just grab a person by the heel and follow your instincts. That’s not dancing—that’s a crime scene. Also, who grabs anyone by the heel?

“Take your baby by the hair / Pull her closer, there, there, there.”

He obviously wasn’t dancing with no sistahs in that dance hall. Try grabbing a Black girl by the hair and you might end up with a fist full of weave…and a broken jaw.

“Take your baby by the wrist / And in her mouth, an amethyst.”

Wait, what's an amethyst? Is it some kind of rock? So now she’s got rocks in her mouth? Are we dancing or burying her alive? This went from weird to full-on Dateline NBC.

Why didn’t the authorities release the dogs on these dudes and take them into custody?

Well… probably because whoever writes a song this good deserves his freedom. “Dance Hall Days,” for all its questionable lyrics, rides along on that blissful synth line, percolating bass, and string flourishes that feel like a soft breeze blowing through a pastel-filtered dream sequence. That Roger Federer-looking lead singer came across as both wistful and just a touch unhinged, selling the vibe like he’s recalling a beautifully choreographed felony from long ago.

Creepy or not, "Dance Hall Days" is a bop. A problematic bop. But a bop, nonetheless.

249

Kylie Minogue

"Slow"

2003

“Slow” sounds like the soundcard of the coolest Atari game you’ve never played.

Kylie Minogue might not be the Aretha of dance music, but she knew exactly how to approach this track: breathy, coy, and light enough not to disturb the song’s sleek, interstellar vibe.

Created in collaboration with acclaimed U.K. producer Dan Carey and Iceland’s second-greatest export (after Björk), Emilíana Torrini—yeah, I had to Google her too—“Slow” is a minimalist, synth-drenched slow-burner that somehow sounds both futuristic and sensual. The bass-heavy, jittery beat breakdown? Pure ear candy. Actually, it’s orgasmic.

But let’s talk about what’s really wrong here: U.S. Americans. This song obviously deserved its #1 spot on the U.S. Dance charts. But how, in the name of all that is holy, did it stall out at #91 on the Hot 100? Meanwhile, Minogue's bubblegum abomination “The Loco-Motion” reached #3? Don’t make a lick of sense, Gringos. Were ya'll mad at Kylie's "Slow" video with all those extremely fit, Speedo-clad people at the public pool squirming around in a sensual manner? You knew that with so many people in that good of shape in one place, the video was obviously filmed outside the United States. America first, I guess.

Voting a ridiculous and unhinged reality star into the office of the presidency TWICE actually makes more sense to me now.

248

Don Henley

"The Boys of Summer"

1984

Was there anyone who DIDN'T have a big hit in 1984? At this point, I’m starting to feel like my own platinum album from that year should be arriving in the mail any day now.

You know me—I’ll find a way to bring up Prince no matter what, and there’s actually a legit connection here. The demo for “The Boys of Summer” was written by Heartbreaker Mike Campbell on a LinnDrum machine and an Oberheim OB-X synthesizer—the same tech that Prince used to make magic on "1999". The reason a classic rock band like the Heartbreakers was even dabbling in electronic gear was because Tom Petty had been listening to Prince and realized he’d need to evolve the band’s sound for their upcoming "Southern Accents" album.

But when Campbell presented this demo to Petty, he politely dropped it in the trash chute. Not sure if Don Henley was rummaging through the dumpster behind Heartbreaker Studios or what, but somehow he got his hands on it, added some cryptic, wistful lyrics—and the rest is music video history.

From those artificial cymbals and moody synths to the ghostly guitar licks, “The Boys of Summer” is one of those songs that gives you that glorious, ominous 80s feeling. Like something sad and beautiful is just around the corner. And I live for that feeling.

And I’m glad that Henley dug this track out of the trash and sang on it because his vocals give the song more texture than Petty ever could’ve. And “The Boys of Summer” is yet another reason why 1984 might be the coolest year pop music has ever seen.

All thanks to Prince… of course.

247

Elton John

"Daniel"

1973

Elton John and his big, oversized clown glasses were an unstoppable force in the 1970s, racking up Top 10 hits and albums like nobody’s business. He probably has something like 10 number-one singles in the U.S.—but let’s be honest, nine of those are just reissues of “Candle in the Wind” every time a famous woman kicked the bucket.

Originally a tribute to Marilyn Monroe, Elton would read the obits, rush to the studio, and turn “Goodbye Norma Jean” into something more topical, depending on who’d bit the dust that week: